We assess that a weeks-long military crisis on the Korean Peninsula is highly likely this year leading to temporary operational and travel disruption as well as short-term volatility in financial markets

This assessment was issued to clients of Dragonfly’s Security Intelligence & Analysis Service (SIAS) on 11 January 2023.

- North Korea fired more than 200 rounds of artillery near a contested maritime border region on 5 January

- Still, we assess that a war between the two is a highly improbable scenario in 2024

North Korea no longer appears interested in peaceful unification with South Korea. There have been several recent signs that Pyongyang is abandoning its previous policy stance towards the South; unification. Military tensions between the two are at their highest in years following a series of escalatory steps by Pyongyang over the past year. And unlike during past periods of tension, there appear to be fewer avenues for de-escalation. As a result, we assess that a weeks-long security crisis in the peninsula is a highly likely scenario in 2024.

Such a crisis would most probably take the form of limited military action by North Korea followed by a few weeks of heightened military tensions. For example, aimed at a group of South Korean islands in the Yellow Sea located about 10-12km from North Korea. And it would result in temporary operational disruption including to regional air and maritime traffic. General elections in South Korea on 10 April and three planned launches of military satellites by North Korea are probable flashpoints.

Inter-Korean relations worsening

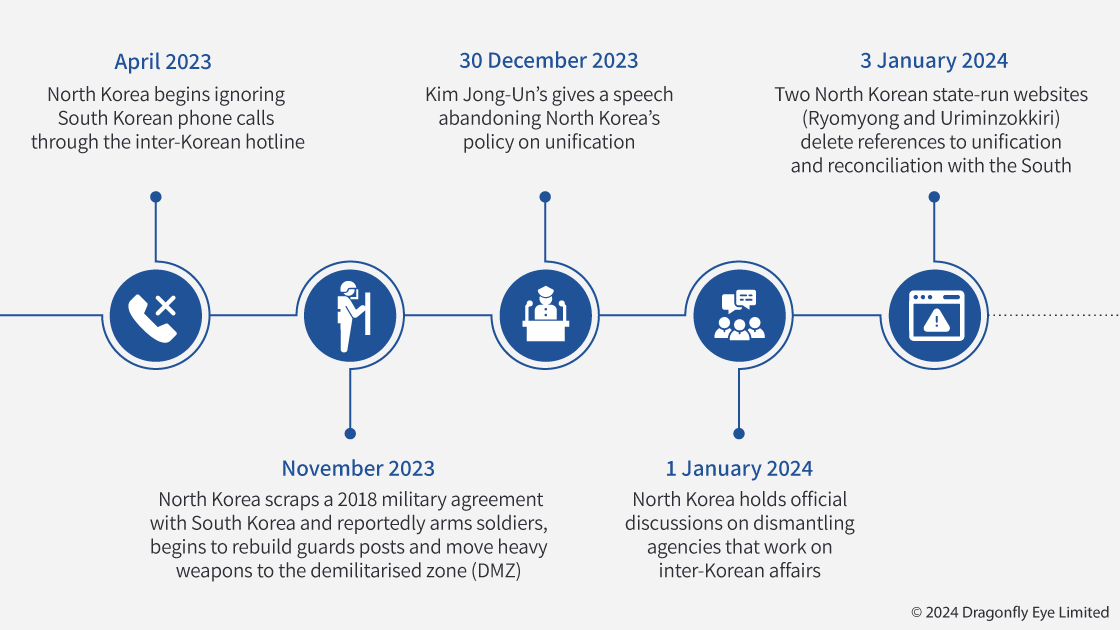

Relations between North and South Korea have worsened to the lowest point in years. Pyongyang has taken several steps in the past year that suggest its intent towards the South is changing and that it no longer perceives unification as its goal. This was particularly evident in a speech by North Korea’s leader Kim Jong-Un in December 2023 where he said the country will no longer pursue ‘reconciliation and unification’ with South Korea, calling it a ‘hostile’ nation. Those steps include:

The South Korean government is also adopting a less tolerant approach towards the North compared with recent years. The previous Moon administration had pushed for inter-Korean peace talks and de-escalation during periods of escalation. But the current government has instead responded tit-for-tat to the North’s actions. Most recently, Seoul said on 8 January that ‘there is no buffer zone anymore’ with North Korea after the two engaged in live-fire drills near their contested maritime border, Northern Limit Line (NLL), last week.

The South Korean government is also adopting a less tolerant approach towards the North compared with recent years. The previous Moon administration had pushed for inter-Korean peace talks and de-escalation during periods of escalation. But the current government has instead responded tit-for-tat to the North’s actions. Most recently, Seoul said on 8 January that ‘there is no buffer zone anymore’ with North Korea after the two engaged in live-fire drills near their contested maritime border, Northern Limit Line (NLL), last week.

In our analysis, any future crisis triggered by Pyongyang would most likely be aimed at being recognised as a nuclear state. As a part of this, the North would probably try to obtain concessions from Seoul, such as the withdrawal of the US forces. Past similar escalations triggered by Pyongyang (most recently in 2017) seemed to be aimed at obtaining sanctions relief from the US but were largely unsuccessful. Since then, the North has appeared emboldened by improving relations with China, Iran and Russia. Those have given it access to added material and diplomatic support.

A military crisis in 2024 is highly likely

On current indications, it is highly likely that the escalatory cycle between the two Koreas will culminate in a weeks-long military crisis this year. By amending its policy aimed at unification, Kim appears to be laying down the ideological groundwork for such a crisis. But there are also material conditions in place that make that probable. This is particularly in regard to the scrapping in November of a 2018 military pact that was designed to prevent provocative actions; South Korea said this week it will resume military exercises in buffer zones that were suspended under the pact.

Both Koreas are also asking their militaries to be more prepared. Kim Jong-Un on 31 December called for a readiness posture as the country is ‘inching closer to the brink of armed conflict’. And South Korea’s defence minister this week called on the military to improve its defence posture and boost combat capability. Actions by Seoul that could plausibly trigger escalation include South Korea sending propaganda balloons into North Korea or turning on loudspeakers at the border. We anticipate that military tensions will run particularly high are the following events:

General elections in South Korea on 10 April: The South Korean authorities have in the past month warned of a ‘high possibility’ of North Korea conducting military exercises, cyber-attacks and ‘psychological warfare’ around the polls

Launches of military satellites by North Korea: In December Pyongyang said it plans to launch three military satellites in 2024. It did not specify a timeline but a satellite launch in 2023 led to South Korea suspending a part of the (now abandoned) 2018 military pact

A crisis scenario; attack in the Yellow Sea

A military crisis would probably take the form of a limited military action by Pyongyang against South Korea. This would most likely be attacking disputed islands with rocket artillery fire, given their geographical proximity to North Korea and the presence of civilians (unlike the DMZ). In our analysis, this would be aimed at Yeonpyeong Island (located in the east of the Yellow Sea, around 12km from the North), Baengnyeong Island (located closest to the North at around 10km) or Daecheong Island. The North has long disputed the position of the NLL that surrounds these islands (see map).

In this scenario, South Korea’s army would be on a heightened alert for a further attack by the North and retaliate by conducting its own launches. There is precedent for this; in 2010 North Korea fired artillery at Yeonpyeong Island killing two soldiers and two civilians. South Korea retaliated by firing artillery towards North Korea. This period would also probably involve further seemingly provocative actions by both sides such as North Korea flying surveillance drones into South Korea, including Seoul.

In this scenario, South Korea’s army would be on a heightened alert for a further attack by the North and retaliate by conducting its own launches. There is precedent for this; in 2010 North Korea fired artillery at Yeonpyeong Island killing two soldiers and two civilians. South Korea retaliated by firing artillery towards North Korea. This period would also probably involve further seemingly provocative actions by both sides such as North Korea flying surveillance drones into South Korea, including Seoul.

Such a crisis would affect operations and travel in Asia. This includes suspension of local trains, closure of tourist sites and potential flight delays and cancellations, particularly in the event of Pyongyang conducting missile firings or using drones to disrupt the airspace in the South. In addition, the threat of nuclear action by North Korea (albeit very low) would plausibly lead to volatility in financial markets, local currencies and indices. The crisis would also narrow evacuation options by air, but not exclude it completely.

War still highly unlikely

We assess a war between North and South Korea is highly unlikely this year. In our analysis, Pyongyang would probably consider this scenario should it perceive that its regime is being directly threatened, most likely by a US-South Korea joint action. And we strongly doubt that either the US or South Korea are currently intent or willing to consider the major humanitarian and economic consequences that such action would bear. In such a conflict scenario, North Korea would probably rapidly resort to escalation, including a potential use of non-conventional, including nuclear, weapons.

Image: South Korean marines lock the entrance to a beach on Yeonpyeong island, near the ‘northern limit line’ sea boundary with North Korea on 8 January 2024. Photo by Jung Yeon-Je/AFP via Getty Images.