Authoritarian governments are likely to be more persistent in targeting individuals working in journalism and NGO’s with spyware at home and abroad in the coming years.

This assessment was issued to clients of Dragonfly’s Security Intelligence & Analysis Service (SIAS) on 24 June 2024.

- Spyware is usually deployed through spear-phishing campaigns – where the victims receive targeted messages containing malicious links

- We assess that the authorities in Egypt, India, Indonesia, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia are particularly likely to use these capabilities to gather intelligence on those working on politically sensitive topics

Individuals working in sectors such as journalism and NGOs in certain countries are likely to be exposed to a high risk of surveillance from spyware in the coming years. This is particularly true for those who work on topics considered sensitive by authoritarian governments, often relating to human rights issues, political exiles or government corruption. These tools are commercially available and their use by governments is becoming widespread. Organisations and individuals are highly likely to struggle to prevent and identify spyware on devices.

We have identified several countries where the authorities appear particularly motivated to use spyware arbitrarily against individuals and organisations in the coming years. These include Azerbaijan, Egypt, Indonesia, Jordan, Kazakhstan and Saudi Arabia. Investigations by research groups have revealed the use (or suspected use) of spyware against government critics by these authorities in recent years – both in-country and abroad. And these countries have multiple verified reports of purchasing or using spyware, for intelligence and data gathering.

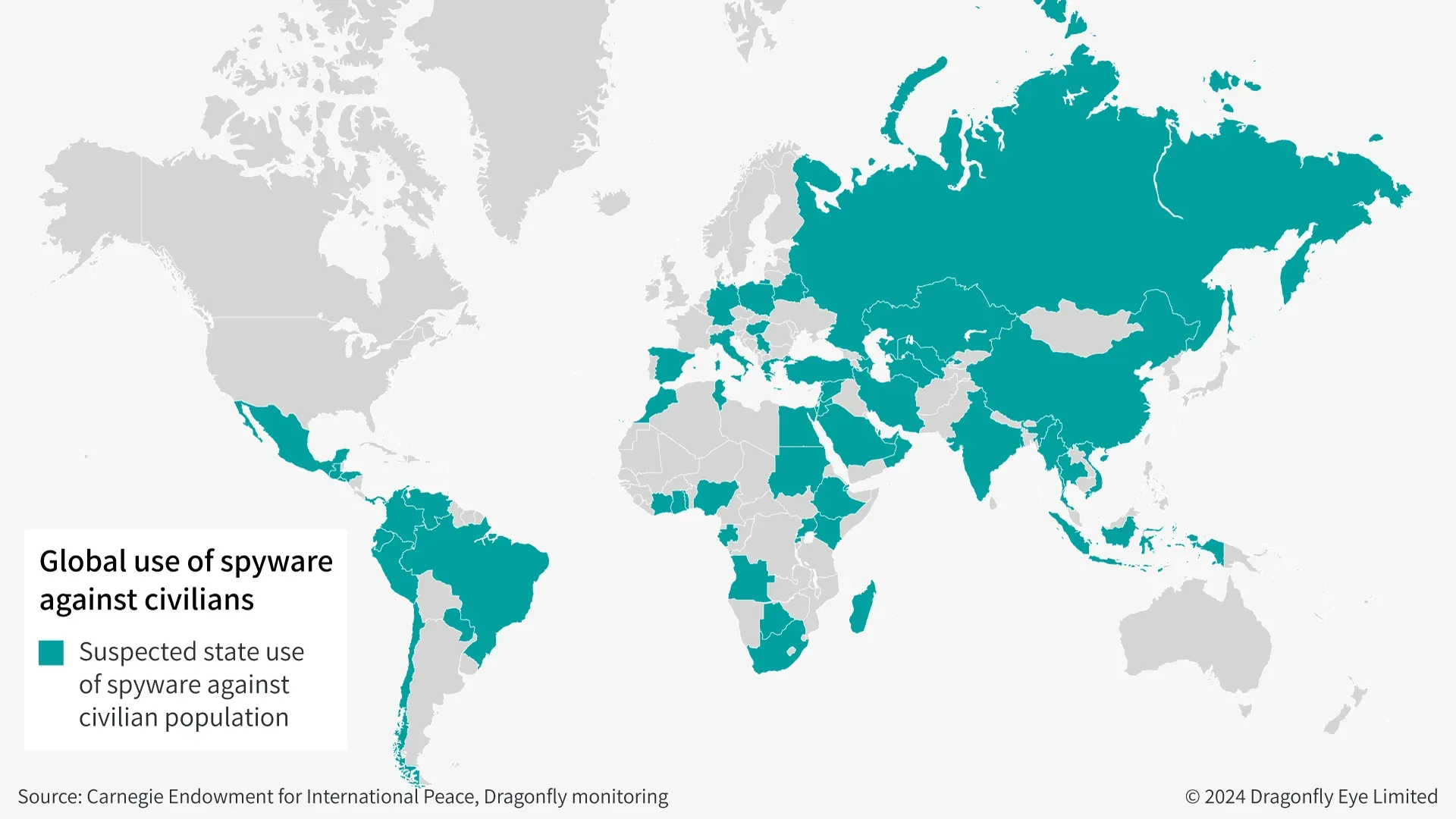

Authoritarian governments and the growing accessibility to spyware technology are likely to lead to worsening personal cyber risks in several countries. The map above shows the countries suspected of using spyware against their citizens for politically motivated intelligence-gathering. This is based on datasets on commercial spyware use and research from organisations such as CitizenLab. But given the lack of transparency around the issue, the actual number of states that possess and use this technology is probably higher.

Countries with high risk of spyware surveillance

Based on cases of spyware in the past few years, and our understanding of the authorities there, we have highlighted several countries where the use of spyware appears most likely. These are Egypt, India, Indonesia, Jordan, Kazakhstan, and Saudi Arabia. These are countries where there appears to be limited rule of law and a lack of transparency on how security forces use surveillance tools. In the past year, human rights groups said that spyware targeted at least 35 civil society members in Jordan. And last year, Apple told several politicians in India that they may have been targeted.

Of the countries we highlighted, the authorities in Saudi Arabia are probably the most motivated and capable of using spyware to monitor citizens and dissidents. This is based on its extensive history of surveillance and detention of critics. It has previously targeted human rights lawyers, activists and journalists. Research group Citizen Lab said that dissidents globally and also a New York Times journalist were targeted with Saudi-linked Pegasus spyware purchased from the NSO Group in 2018.

The risk of exposure to spyware is likely to be heightened in many countries ahead of elections, or during major protest movements. This is when the authorities would be most intent on monitoring and silencing critics. In one recent example, a cybersecurity firm said in October 2023 that it is ‘plausible’ that the authorities in Madagascar used Predator spyware to ‘conduct political domestic surveillance, months before the election’. It was not clear who this was intended to target, although a presidential election was held on 16 November.

Priority targets globally are local activists and critical journalists

Governments globally appear most likely to target locals working in sensitive sectors, such as activists and journalists. That is based on reported cases, which suggest that dissident nationals now living abroad are also frequently targeted, but slightly less. This is probably as these people are viewed by governments as posing the greatest threat to regime stability. But this does not preclude foreign nationals from being targeted, either while in the country or abroad. And some governments appear to have targeted prominent foreign politicians as part of their intelligence-gathering.

Government agencies in authoritarian countries appear to use such tools to conduct extensive surveillance of critics to silence and discredit them. Individuals targeted by spyware have been detained and had their conversations edited and leaked. Once the device is infected with the spyware, the perpetrator can monitor the target’s messages, calls, photos and location. This includes accessing encrypted apps or messaging services.

The deployment of spyware against the devices of individuals in commercial sectors will probably remain limited in the coming year. In most cases where individuals in the private sector have been targeted, they have been linked to prominent opposition politicians or activists. In a rare case, in March 2023 the New York Times reported that Greek authorities had targeted the device of a US-Greek security and trust manager of a multinational tech company in 2021. But people not directly involved in politics or activism can also get caught up in electronic surveillance.

Persistent risk of electronic surveillance

At-risk individuals and organisations are highly likely to struggle to prevent and identify spyware targeting their devices in the coming years. An international organisation which aims to protect journalists has advised their members who may be targeted to frequently back up and carry out factory resets of their phones, and to update devices and apps regularly. But this is unlikely to completely prevent compromise in the coming years. Given the intent of governments and the profitability of the industry, there is an incentive for vendors to continue to develop new exploits to target devices.

Image: A member of the hacking group Red Hacker Alliance who refused to give his real name, uses a website that monitors global cyberattacks on his computer at their office in Dongguan, China’s southern Guangdong province , on 4 August 2020. Photo by Nicolas Asfouri/AFP via Getty Images.