- A global expansion of scam centres will probably continue to drive high rates of cybercrime over the next few years

- On 5 August, Meta said it took down over 6.8m WhatsApp accounts ‘linked to criminal scam centres’

- Local and international authorities will probably struggle to dismantle such centres in the coming years

An ongoing global proliferation in scam centres is likely to continue driving high rates of cybercrime in the coming years. In a recent sign of this, Meta said on 5 August it took down over 6.8m WhatsApp accounts ‘linked to criminal scam centres.’ And Interpol said on 30 June that the presence of scam centres run by criminal groups is expanding globally.

Organised crime groups have reportedly trafficked hundreds of thousands of individuals to these compounds, mainly in Southeast Asia. Based on their past operations, criminals based in scam centres are likely to attempt to steal data from firms or force their employees into conducting fraudulent transactions.

Local and international authorities will probably struggle to combat or dismantle scam centres in the coming years. Groups running these seem highly capable of establishing and running operations in areas of weak governance, and leveraging AI to increase recruitment and efficiency. Criminals based in scam centres also often target countries outside the one they are based in, meaning the authorities have little domestic pressure to conduct crackdowns. And international awareness of the issue appears limited.

Scam compounds proliferating globally

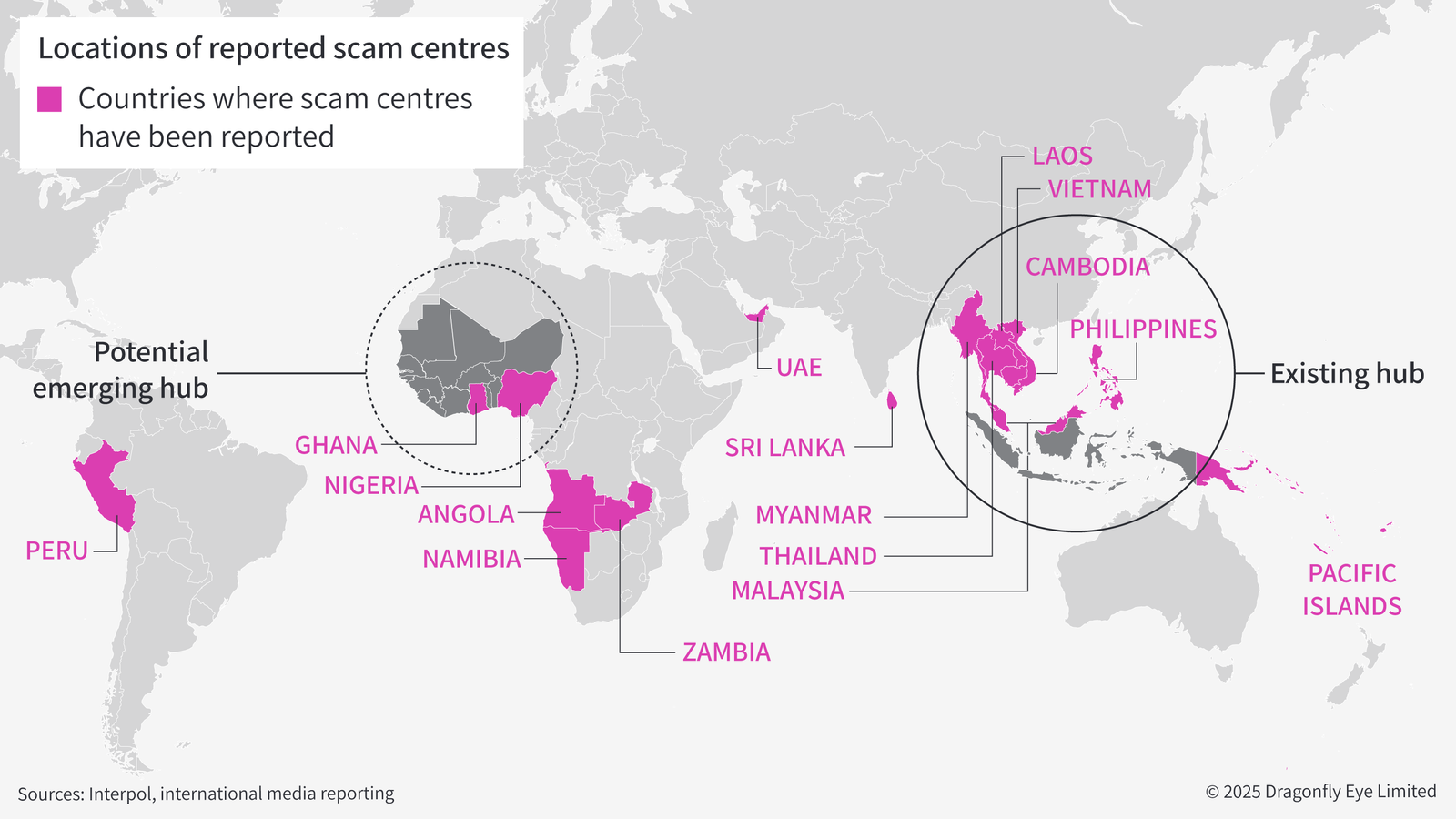

The model of cybercrime scam centres is expanding in use globally, according to two recent reports by Interpol and the UN. Southeast Asia, particularly Myanmar, has been a hub for scam compounds in recent years (see B-THA-30-01-25 for more on Thailand). Interpol said in a report from June that victims from 66 countries were trafficked into such centres as of March 2025, and that scam centres have ‘increasingly been observed’ in regions outside of Southeast Asia.

In particular, Interpol identified West Africa as a ‘potential emerging hub’ for such centres. In our analysis, Nigeria appears likely to be a hotspot due to already high levels of cybercrime from domestic groups, based on available cybercrime data. Human trafficking also appears to be facilitating cybercrime in the region. According to a 2023 charity report, several individuals from Nigeria were trafficked into Ghana, where they were forced to meet daily scamming targets.

Based on identified cases in Southeast Asia and elsewhere, centres are likely to run uninterrupted in areas where there is a lack of governance. Cybercriminals establishing such centres also appear to set them up in areas with porous borders, as this is where existing criminal networks are already present and where workers can be easily trafficked across borders. Cybercriminals seem to be heavily dependent on trafficked workers, whom they can exploit, given that scam centres rely on a large number of workers.

Cybercrime targeting firms and individuals

There is no available data on the percentage of global cybercrime that is linked to scam compounds. This is likely due to difficulties in attributing campaigns to specific groups. But scam centres seem to be prolific in conducting cybercrime. The United States Institute of Peace estimated that the groups behind scam compounds in Asia stole nearly $64 billion globally in 2023, according to a 2024 report. The US seems to be a particular priority for groups based in scam centres; one scam centre leader said to Sky News that the country is a main target due to its wealth, according to a 2024 report.

Tactics used by cybercriminals in scam centres

Scam centre groups seem to use particular tactics to target victims, such as social engineering to trick victims into transferring money or making fraudulent investments. This includes business email compromise scams, where scammers impersonate senior employees to manipulate others into transferring funds, and phishing campaigns. They also tend to carry out long-term manipulation of individuals to send them cryptocurrency for fake investments (known as ‘pig butchering’). This is based on a number of reports from think tanks and international organisations.

It seems likely that these tactics will become more common in the coming years as such centres expand their operations. Such tactics are relatively unsophisticated compared to other cybercriminal methods, as scam centre groups seem to be using trafficked workers with little cybercrime experience.

That said, the use of AI by such groups is likely to enhance the sophistication of such scams in the coming years. Criminal groups have reportedly used AI to translate messages, create videos and audio to be used during scams, and to create fake job descriptions to lure workers to join their centres. It is also likely that such groups will use AI to assist with basic coding tasks, leading them to more frequently deploy malware to steal data or access banking apps.

Authorities likely to struggle to combat centres

The cross-border nature of scam centres and their prevalence in insecure areas will probably mean that the authorities struggle to shut them down. Additionally, the reliance on human trafficking means that it is difficult to trace the scam networks. This is especially in Southeast Asia, where the criminal groups have proven to be agile in relocating after previous law enforcement operations. In a sign of this, a July report from news outlet Nikkei Asia said that despite a crackdown on scam compounds in eastern Myanmar in February, the construction of compounds is still expanding ‘at a rapid pace’.

This pool photo taken on July 17, 2025 and released on July 18 by Agence Kampuchea Presse (AKP) shows military police looking at computers, smartphones and other equipment seized during a raid on a scam centre in Kandal province. The number of suspects arrested in a Cambodian crackdown on internet scam centres has risen to 2,000, a government minister told AFP on July 18. (Photo by POOL / AFP)