- An acute security crisis in Tripoli appears likely in the coming days or weeks, as the Government of National Unity (GNU) moves against a rival militia

- Intense inter-militia clashes would be likely to affect densely-populated areas and key infrastructure, including the airport

- Evacuation options are limited, necessitating early-warning systems and robust shelter-in-place plans

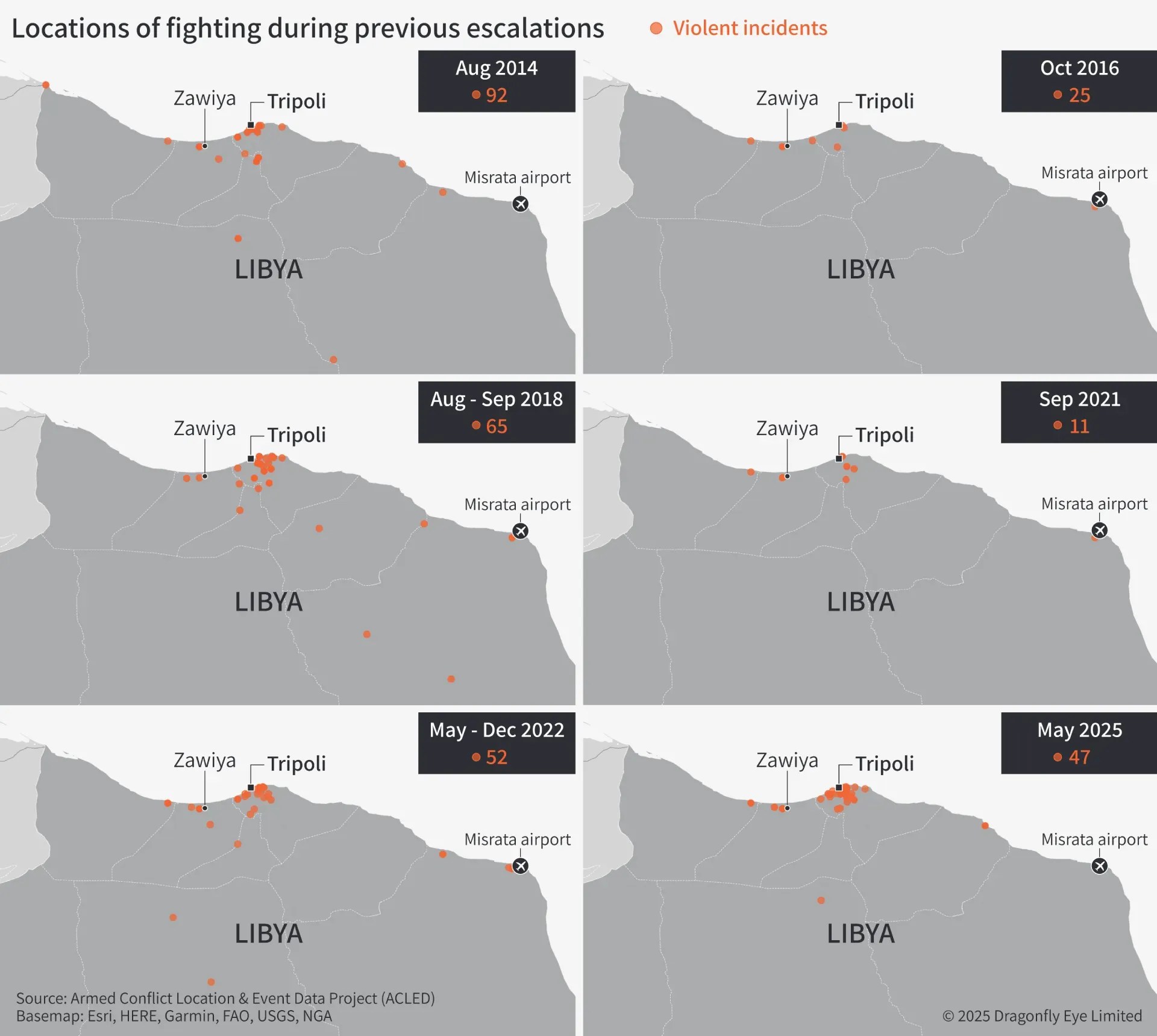

An acute security crisis in Tripoli appears likely in the coming days or weeks. Militias aligned with prime minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah’s Government of National Unity (GNU) have mobilised and moved towards the capital in recent days, threatening an attack on the rival Special Deterrence Forces (SDF, also known as Rada). Some clashes took place over the weekend, both in Tripoli and nearby cities, and the dispute between the GNU and SDF remains unresolved. A GNU assault on the SDF is likely, which would probably lead to intense clashes lasting up to several weeks.

Even if the current dispute is resolved, persistent inter-militia rivalries over territory and influence in the capital sustain a severe risk of armed conflict in Tripoli. A fragile truce between rival militias in the capital was disrupted in May when the 444 Brigade, a GNU-linked militia, ousted the rival Stability Support Apparatus (SSA). And ongoing brinkmanship between the Libyan National Army (LNA) under General Haftar in the east and the GNU in the west also sustains the risk of fighting between the two.

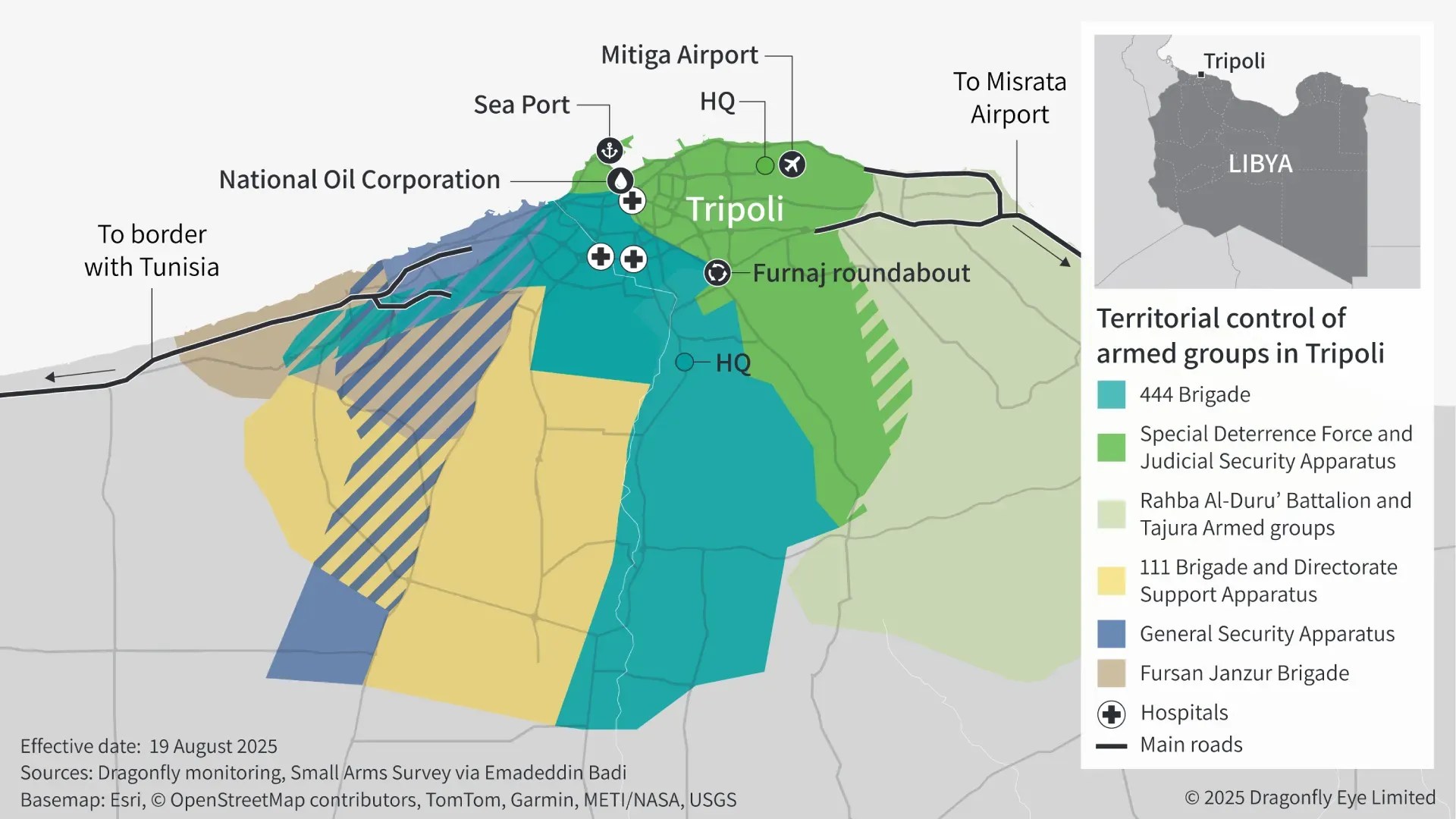

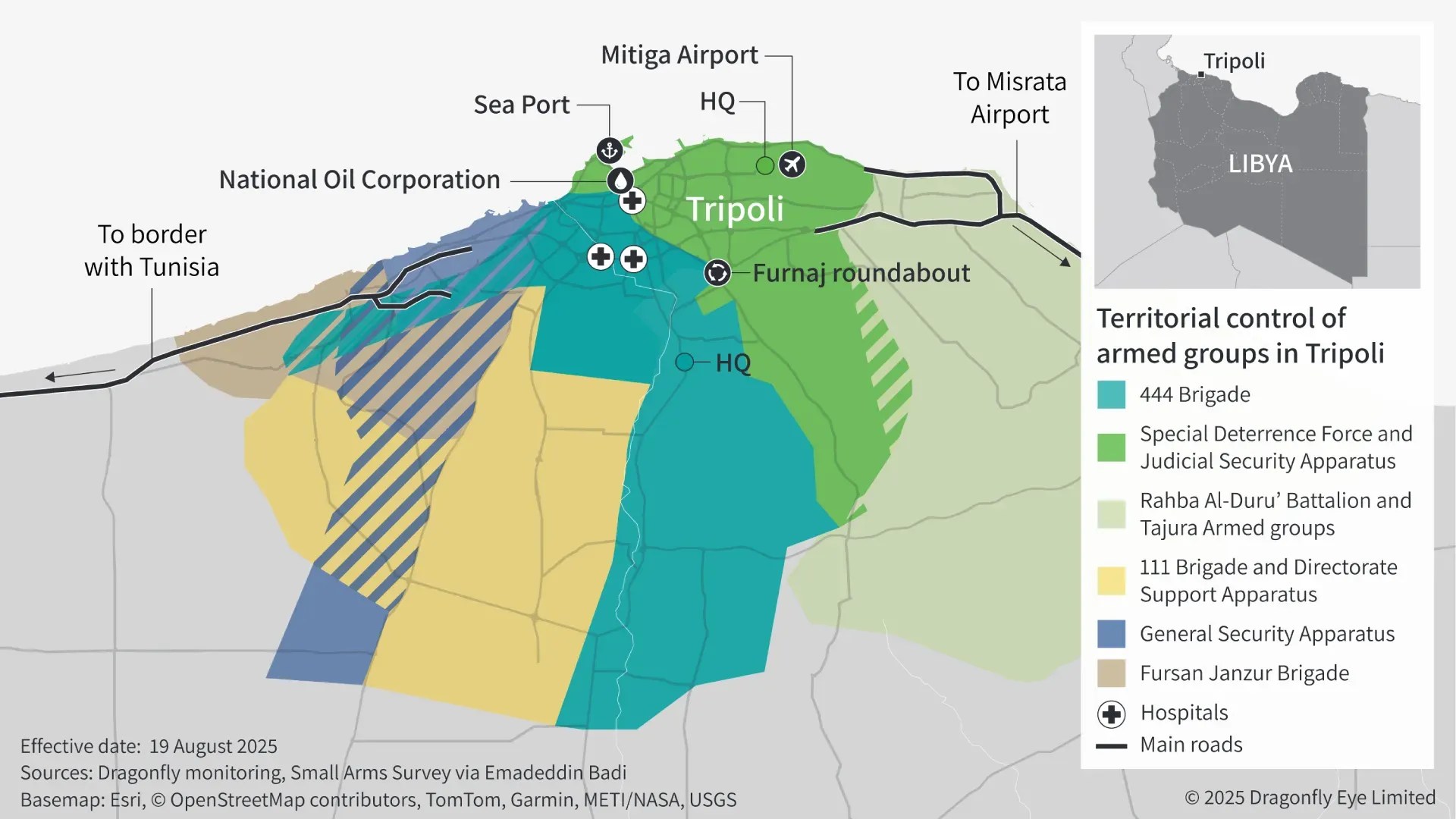

Planning and executing a crisis response operation in Tripoli is challenging. Given the presence of several competing militias, governance and security structures in the city are highly fragmented. The fragile equilibrium that exists in the city would almost certainly disintegrate in the event of an acute crisis, meaning that clashes would probably impact multiple neighbourhoods. This, and restrictive access controls between areas, would make movement very dangerous. Control of critical infrastructure sites, such as Mitiga International Airport, is often contested during escalations, complicating evacuations.

This report provides crisis and contingency planning information for Tripoli based on the current operating environment, and its probable changes in a crisis. We set out the most plausible acute crisis scenario for context, but the focus of this report is tactical considerations relevant for planning and managing all types of acute crises. Such considerations include: movements, evacuation, sheltering-in-place and communications.

Inter-militia clashes most likely crisis scenario

We assess that an assault by GNU-linked forces on the rival SDF is likely in the coming days or weeks. In May, the GNU-aligned 444 Brigade ousted one of its two main rival armed groups in the capital. It then tried to push on and moved against the SDF, but was thwarted. The groups then agreed to a ceasefire, which – despite near-weekly recurring armed clashes and shootings in the capital – has held so far.

But the ceasefire now appears to be unravelling. There are signs that GNU-linked security forces are preparing a major offensive in Tripoli; several militias have mobilised and moved towards the capital over the past week, following weeks of armed clashes and assassinations of rival militia leaders in the surrounding region. Dbeibah recently demanded that the SDF hand over strategic sites such as Mitiga airport and the prison there. SDF has refused. Small-scale armed clashes took place in the capital, including in the Abu Salim neighbourhood south of the city centre, overnight on 31 August – 1 September.

Fighting would probably take place across central Tripoli, and particularly around sites critical for evacuations, such as the port in central Tripoli and Mitiga airport to the east. These are key strategic sites, control over which would almost certainly be contested among militias. But clashes are unlikely to be limited to Tripoli. Militias in nearby cities such as Zawiya have tended to mobilise during such other escalations in support of pro or anti-GNU forces, and we have seen little to suggest they would do differently this time. Their involvement would almost certainly complicate potential exit routes out of Tripoli.

Indicators that clashes in Tripoli are imminent

- The 461st Battalion, a militia that is enforcing the ceasefire, withdraws from Tripoli

- Foreign governments or the UN (UNSMIL) warn of an escalating security situation and advise citizens to leave immediately

- The GNU or the SDF publicly state that any informal talks aiming to resolve the standoff have collapsed

- Militias in the capital announce overnight curfews

- Airlines evacuate planes from Mitiga airport

- Armed groups move heavy weaponry, including artillery and tanks, toward contested areas in the capital, such as Mitiga and militia HQs

- Further reinforcements from nearby cities move into the capital

- Local media outlets report on assassination attempts of key militia leaders (SDF or 444 Brigade in particular)

- Rival armed groups erect roadblocks or clash on key routes into the capital

Movement becomes dangerous quickly

In the event of inter-militia clashes, movement across Tripoli would almost certainly become dangerous and highly restricted quickly. Armed groups control key areas and infrastructure throughout the city, including central neighbourhoods and major coastal routes. Militias are heavily armed, and major groups like the 444 Brigade and the SDF are each estimated to field around 1,500–2,000 fighters. Clashes in Tripoli frequently involve the use of heavy weaponry in densely-populated areas; in May, artillery strikes hit militia positions and civilian infrastructure in residential neighbourhoods.

Fighting would probably be concentrated in contested zones along militia frontlines (see the map below), as well as around strategic sites such as militia headquarters, the port, and Mitiga International Airport. Clashes would also likely spill into the southern suburbs. This fragmented control raises the risk of simultaneous and sudden outbursts of violence across the city, severely limiting safe routes and making cross-city movement highly dangerous.

The authorities would also probably impose curfews during periods of sustained intense violence, further limiting movement options. In an example of this, the GNU declared an overnight curfew across central Tripoli during clashes between the 444 Brigade and the SDF in May. Such restrictions would compound access constraints, hinder evacuations, and limit the ability of responders or residents to relocate safely. We do not know which, if any, would make formal exemptions for foreigners. This is because different groups control different checkpoints, and enforcement of any such directive is likely to be inconsistent and unpredictable.

Evacuations

Air and sea routes offer the fastest options out of Tripoli during a crisis. But exit points for both are very likely to become inaccessible early in a serious escalation. Mitiga International Airport and the port are key strategic sites and probable focal points for clashes, making their use highly uncertain. If these become inaccessible, land evacuation would be the only alternative to sheltering in place. But road travel in Libya is challenging. The route to Tunisia through Zawiya is dangerous even in peacetime, with a high risk of carjacking, robbery and violence at militia checkpoints.

Considerations for evacuations by air

Mitiga International Airport in the northeast of the city remains the only operational airport for international flights out of Tripoli. This has been the case since Tripoli International Airport, some 30km south of the city, was severely damaged during fighting in 2014 and 2019. There are no direct flights between Tripoli and Europe. But several regional airlines, including Egyptair, Royal Jordanian and Turkish Airlines, operate near-daily flights to and from cities such as Amman, Cairo, Istanbul and Tunis.

Operations at Mitiga airport are highly vulnerable to major disruption during periods of conflict. It is currently under SDF control, whose headquarters are by the airport. It is often a key focal point during major bouts of armed fighting, with rival militias threatening or mounting attacks against the airport. This usually leads to delays or suspensions of flights.

Carriers tend to preemptively evacuate their aircraft from the airport to prevent them from being damaged; they also did so during the clashes in May this year. Operations are often rerouted from Misrata International Airport (MRA). This airport, located some 200km east of Tripoli, is typically more reliable during a crisis. If the road is not blocked, the drive between Tripoli and Misrata takes around two and a half hours along the Coastal Road (Route 1). There is a reasonable possibility that pro-GNU militias operating in this area would demand bribes for passage at checkpoints.

The GNU in July announced the resumption of medical and private flights at Tripoli International Airport (TIP). With the airstrip now operational again, chartered evacuation flights might be possible from here during a crisis. This would likely involve securing landing and take-off clearance from the Libyan authorities, as well as non-state military actors.

Considerations for evacuations by sea

Should evacuations by air prove impossible, Tripoli’s seaport presents an alternative exit route. It has commercial docking capacity suitable for medium to large vessels and could be used for private marine extraction or government-coordinated evacuations if access is secured in time. Its reliability in a crisis is uncertain. The port is a key strategic asset and likely flashpoint during escalations. The GNU controls the port, but rival armed groups control the surrounding areas. In May, fighting near the port caused a full suspension of operations for several days.

Sea evacuations would likely involve either naval deployments coordinated with European states or privately-contracted vessels. NATO or EU member states, particularly Italy, coordinated extractions during heavy inter-militia clashes in 2014 and armed conflict between the GNU and General Haftar’s Libyan National Army in 2019. Private marine evacuations could plausibly also be arranged. Probable embarkation destinations include Valletta (Malta), Zarzis (Tunisia) or Larnaca (Cyprus), though all would require pre-coordination and secure transport to the dock.

A trusted security contact experienced in evacuations suggested that tenders could also be used for boats to pick up people along the coast. The coastline itself is physically accessible in many areas. But reaching it would involve crossing the Coastal Road, which is often contested or blocked by armed groups during escalations.

Considerations for evacuations by land

If air and sea routes are unavailable, road evacuation westward toward Tunisia would become the only remaining exit option. The direct route runs along the Coastal Road through Zawiya and Sabratha to the Ras Ajdir border crossing. However, this stretch is particularly dangerous, even in peacetime.

Multiple armed groups, including militias from Zintan and Misrata, control sections of the route and operate checkpoints where travellers may face extortion, detainment or robbery. We understand that this option is only viable with local fixers who can organise vehicles and passage at checkpoints. The Ras Ajdir crossing itself becomes a major bottleneck during crises, leading to hours-long delays if not more.

An alternative route runs southwards from Tripoli through Gharyan and towards Tunisia via Nalut and the Dehiba-Wazen crossing. This route is longer than heading west. And it has also been a theatre for fighting during previous escalations. The road is strategically important and could be used again as a supply route or mobilisation corridor in the event of heavy inter-militia clashes or a broader east-west conflict. As a result, checkpoints by armed groups would be likely on this route as well.

Shelter-in-place challenges

With evacuation options limited, individuals and organisations may find themselves needing to order staff to shelter in place for extended periods. Given the high likelihood that violence would affect multiple neighbourhoods and critical infrastructure, periods of restricted movement could last days or even weeks – necessitating a few weeks’ worth of essential commodities such as food, water, fuel and medical provisions. We have not seen reports about major shortages yet. Generators and fuel reserves – which seem still readily available – can mitigate power cuts.

Communications

Mobile phone coverage and network strength in Tripoli are generally good under normal conditions, particularly in central areas. However, coverage can become unreliable during periods of crisis. Government authorities and militias have repeatedly shut down internet and phone networks during clashes or unrest (including after the Derna dam collapse in 2023). Independent communication systems, such as satellite phones, provide a contingency.

Over a decade of civil conflict has set back Libya’s telecommunications infrastructure. This compounds the risk that an extreme weather event, like a major flooding, could damage telecommunications infrastructure or cause power outages, leading to prolonged disruptions in mobile and internet services.

People raise placards as they demonstrate against the Government of National Unity (GNA), in Tripoli on June 20, 2025. Libya has been gripped by chaos since a 2011 uprising brought down and killed longtime dictator Moamer Kadhafi, and is now split between the UN-recognised Government of National Unity (GNA) in Tripoli and forces loyal to eastern-based strongman Khalifa Haftar. (Photo by Mahmud Turkia / AFP) (Photo by MAHMUD TURKIA/AFP via Getty Images)