- We assess that Bangladesh, Myanmar and Pakistan are the countries most susceptible to major civil unrest in Asia into 2026

- Economic hardship and inflation are key underlying drivers of protests, coupled with public anger over widespread corruption

- For companies, unrest will most probably result in operational disruption due to road closures and mobile internet shutdowns; acute crises stemming from unrest in most countries appear unlikely

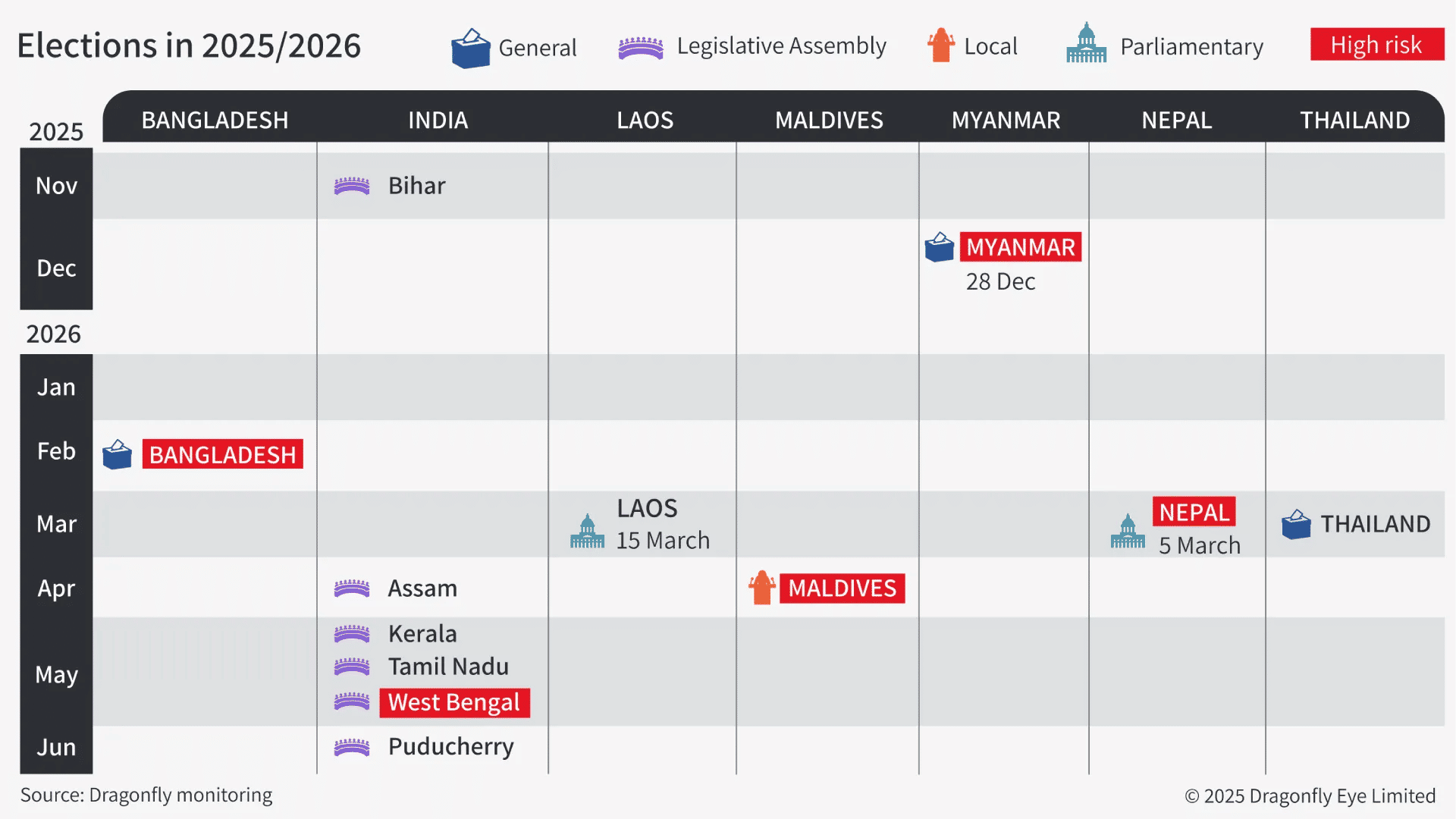

Bouts of civil unrest are likely in several countries in Asia in 2026. In South Asia, persistent economic strain, corruption and public disillusionment with political elites are likely to fuel violent protests next year, especially in Bangladesh, Pakistan and Nepal. We assess that electoral periods, such as the general elections in Bangladesh in February and in Nepal in March, are also key flashpoints for periods of unrest. In Southeast Asia, high-risk countries include Indonesia, Myanmar and the Philippines due to government efforts to pass unpopular economic and governance reforms.

Any civil unrest is almost certain to result in localised operational disruption lasting from a few days to a week or two. This stems mainly from road closures and mobile internet restrictions. While personnel safety risks tend to be high in the immediate vicinity of unrest, business travellers or foreign firms are unlikely to be specifically targeted by protesters or the security forces during these.

Driving conditions of unrest persist

We assess that economic hardship, inflation and limited job creation are the key drivers for unrest in Asia in 2026. Inflation has eased from its peak in 2022 and 2023, but persistent food and fuel inflation still strain household budgets, including in Bangladesh, and drive up anti-government sentiment. Pakistan and Sri Lanka are also likely to implement austerity measures, such as tax rises and fuel subsidy cuts, to fulfil IMF bailout conditions. Opposition parties and youth-led groups tend to capitalise on this, criticising the government for economic mismanagement and calling protests.

Public dissatisfaction over government corruption and disillusionment with political elites is also likely to fuel unrest. Public frustration over perceived corruption in government institutions, high-profile corruption scandals and a weakening of democratic checks have been some of the main reasons for unrest in Asia in recent months, such as in Indonesia and Nepal. And based on our social media monitoring, this has also been deepening over the past year in the Maldives. Several recent academic studies have pointed to limited and perceived unfair access to good jobs being a key frustration, particularly among South Asia’s large and growing youth population.

Countries most at risk of unrest

In South Asia, Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan are likely to be most susceptible to prolonged civil unrest in 2026. This is based on our analysis of economic data, the political context, and recent protest action. In Bangladesh and Nepal, political polarisation remains high following recent political crises, as does youth disillusionment with political elites. In Pakistan, we assess that the widespread flood crisis in 2025 will exacerbate poor economic conditions into 2026 and push up the already high risk of protests and social unrest.

In Asia Pacific, we have identified Indonesia, Myanmar and the Philippines as the countries where unrest is most likely into 2026. Although disruptive protests that took place in Indonesia in late August have now stabilised, underlying drivers of the unrest persist. This includes economic discontent as well as ongoing economic and governance reforms by the new government.

In Asia Pacific, we have identified Indonesia, Myanmar and the Philippines as the countries where unrest is most likely into 2026. Although disruptive protests that took place in Indonesia in late August have now stabilised, underlying drivers of the unrest persist. This includes economic discontent as well as ongoing economic and governance reforms by the new government.

Myanmar has been in a state of crisis since a military coup in 2021. General elections that are currently scheduled in December is a particular flashpoint for unrest there; this is due to deep political polarisation and widespread public distrust in the electoral process. In the Philippines, the overall economy appears resilient. But the government remains under heightened scrutiny by the population amid corruption allegations.

We have identified a list of developments that, in our analysis, would probably signal an imminent and heightened risk of widespread unrest on a country-by-country basis:

- Bangladesh: The interim government delays parliamentary elections (due in February), citing serious security concerns

- India: The government passes controversial legislation affecting large sections of the public, for instance related to minority rights

- Indonesia: The government enacts new reforms aimed at boosting the military’s powers across society

- Maldives: The government defaults on its foreign debt or implements major austerity measures to manage it

- Nepal: Established political parties win the general election (due in March) amid widespread accusations of electoral fraud and police brutality

- Pakistan: Imran Khan, an opposition leader, dies while in custody

- Philippines: President Marcos is personally implicated in a major corruption scandal

- Sri Lanka: The government implements a sharp tax increase or price hike, or an unpopular legislation around pay, working hours or privatisation

Elections as key trigger event

The likelihood of exposure to violent unrest is highest around elections. This is especially in Bangladesh, Nepal, and West Bengal, India. These countries and states have an established pattern of violent protests and politically-motivated bouts of unrest during election cycles. In the weeks ahead of the 2024 general elections in Bangladesh, there was widespread violence between rival activists and security forces in major cities, including Dhaka, countrywide. During the 2024 Indian general election, there was also significant unrest and widespread allegations of electoral fraud reported in Kolkata.

The most common trigger for a peaceful demonstration to turn into violent unrest regionwide has often been authorities using severe force to disperse protesters. During the September unrest in Nepal, the police reportedly fired live rounds at activists who breached security zones in Kathmandu, which led to a major escalation of violence. This was also the case in Bangladesh last summer, when the killing of a student by the police intensified the protests that had been largely peaceful until then, according to international and local press reports.

The most common trigger for a peaceful demonstration to turn into violent unrest regionwide has often been authorities using severe force to disperse protesters. During the September unrest in Nepal, the police reportedly fired live rounds at activists who breached security zones in Kathmandu, which led to a major escalation of violence. This was also the case in Bangladesh last summer, when the killing of a student by the police intensified the protests that had been largely peaceful until then, according to international and local press reports.

Impact of potential unrest

Civil unrest is almost certain to result in localised operational disruption lasting for a few days up to a week or two in 2026. This will likely stem from curfews, other movement restrictions, and aviation disruption. Hours or even days-long road blockades by protesters and road closures by authorities tend to be frequent during large protests. This was the case in Bangladesh and Pakistan recently. In the run-up to the 2024 Bangladeshi elections, recurrent road blockades by the opposition, lasting for several weeks, led to severe supply chain delays at Chittagong Port. And in Nepal, a few days of violent unrest in September also led the authorities to close Kathmandu Airport for about two days.

Regional and local authorities are also highly likely to impose mobile internet shutdowns and restrictions to manage large protests and quell outbreaks of unrest. This is an established tactic in Bangladesh, India, Myanmar and Pakistan. In November 2024, the authorities in Pakistan partially suspended mobile internet access in Islamabad, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab provinces ahead of nationwide opposition protests. Such restrictions are usually imposed around protest locations, but larger scale deadly unrest would probably prompt city or country-wide network restrictions.

Foreigners very unlikely to be directly targeted

Business travellers or foreign firms are unlikely to be specifically targeted during unrest. Protests in the region over the past year have primarily targeted local authorities due to economic and political mismanagement and disillusionment with political elites; we have detected no particular hostility towards foreigners. Still, some major international hotels in Nepal were badly vandalised during the recent ‘Gen Z’ protests. But this appears to have been because activists saw them as symbols of wealth inequality and the political elite, rather than because they were foreign.

Civil unrest is still likely to pose a high risk to bystanders and commercial interests. This is due to security forces often dispersing disruptive demonstrators with tear gas and baton rounds – and sometimes with live rounds – as was the case in Nepal and Bangladesh recently. We have not seen any Western government advising their citizens to leave any Asian country in the recent instances of major unrest. But they have regularly advised citizens to shelter in place and avoid protest areas.

Protesters are also often indiscriminate when attacking security forces. They often throw sticks and petrol bombs at police as well as counter-protesters, putting non-participants in proximity at risk of harm. In Nepal, 72 people were killed and over 2,000 were injured in the two days of unrest. Violent running battles between rival activists, some fatal, are also likely in India and Bangladesh on the sidelines of demonstrations. Risks are still typically highest around protest sites and any government buildings.

Demonstrators wield stones and sticks as they clash with riot police personnel during a protest outside the Parliament in Kathmandu on September 8, 2025, condemning social media prohibitions and corruption by the government. At least 16 protesters were killed on September 8 after Nepal police fired rubber bullets, tear gas and water cannon to disperse demonstrators demanding the government lift its ban on social media and tackle corruption. (Photo by Prabin RANABHAT / AFP) (Photo by PRABIN RANABHAT/AFP via Getty Images)