- Armed groups are likely to intensify attacks on security forces in the coming year to consolidate their recent territorial gains

- These groups seem willing to also accept civilian casualties as part of attacks in major cities; the Estado Mayor Central (EMC) guerrilla group killed six civilians in an explosion outside a military base in Cali last month

- Most armed violence and bombings will probably be concentrated in rural areas

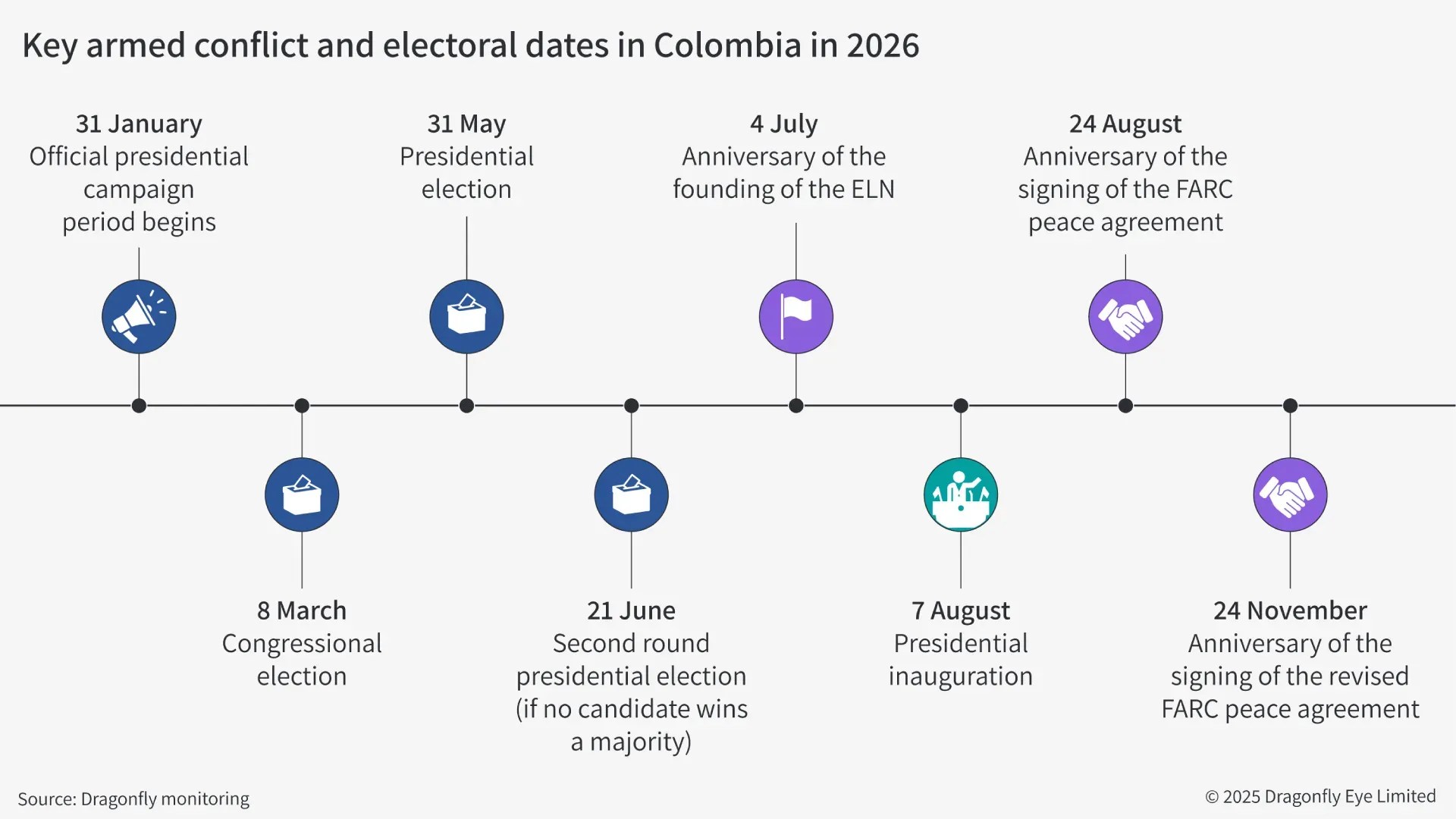

Armed groups will probably intensify the frequency of their attacks against the authorities ahead of a presidential election scheduled for May next year. This is mainly because the government seems to have abandoned its efforts to call for ceasefires with such groups, instead favouring military offensives. And guerrilla groups seem determined to retaliate and enhance their position ahead of the next government taking office in August 2026. They will probably mount attacks primarily in rural areas. But some groups also seem intent on targeting cities, particularly Cali.

Drivers for armed conflict worsening

We assess that the prospects for President Gustavo Petro achieving any major peace deals during the remainder of his term are remote. This year, the government has abandoned its approach of seeking to encourage armed groups to engage in peace talks by first implementing ceasefires with them. Such groups exploited these ceasefires to challenge rivals and expand their drug-trafficking operations. Instead, the authorities have prioritised military offensives against them.

The government has not offered an appealing deal or exerted enough military pressure to compel armed groups into peace talks, though. At most, Petro is likely to secure localised agreements. A recent example is an April deal with a Narino-based faction of the Ejercito de Liberacion Nacional (ELN). Major armed groups are composed of multiple factions with conflicting local motives, making any comprehensive, nationwide settlements highly challenging.

Finally, uncertainty surrounding US support for Colombia will probably also discourage armed groups from talking with the government. Washington on 15 September classified Colombia as a country which has ‘demonstrably failed’ to uphold its obligations to tackle drug trafficking, as part of an annual review. Although this decision is tied to US aid, which the Colombian military is heavily reliant on, the US stopped short of ending this. Regardless, based on our understanding of how armed groups operate, they will probably perceive the government as weak as a result, disincentivising them from seeking talks.

Armed groups seeking to solidify standing ahead of elections

In response to the government abandoning its conciliatory approach, the frequency of armed attacks and bombings is likely to remain high ahead of a presidential election next year (see timelines below). According to our data, guerrilla groups mounted 301 attacks in 2024; in comparison, they have already mounted 243 in the first six months of 2025.

Armed groups will probably seek to consolidate and expand their territorial control to enhance their position ahead of the next government taking office. In particular, this would be through infiltrating local state authorities and achieving a high level of control over rural populations to hinder government efforts to curb them. In a clear example of this last month, residents in a village in the central Guaviare department prevented 33 soldiers from leaving the area to demand the return of the body of a guerrilla fighter killed in combat.

However, armed groups are likely to pursue a strategy of territorial entrenchment in rural areas rather than direct electoral interference. Some press outlets have in recent months suggested that a guerrilla group ordered the assassination in June of Miguel Uribe, a right-wing hardline anti-crime senator, given that he intended to run for president. But we are sceptical of such claims; assassinating political candidates who oppose them would probably only prompt the government to focus its operations against the group that ordered the killing.

Attacks likely in strategically important rural areas

The majority of armed group attacks on the authorities will probably remain concentrated in rural areas that are strategically important for coca production and trafficking. These include the southwestern departments of Cauca, Narino and Valle de Cauca, as well as the northern departments of Arauca and Norte de Santander.

Sporadic attacks are likely in rural areas elsewhere in the country, typically near coca production and trafficking areas. On 21 August, an explosive charge planted by the Estado Mayor de Bloques y Frente (EMBF) guerrilla group in rural Antioquia, about 100km from Medellin, brought down a police helicopter involved in coca eradication, killing 13 officers.

Most attacks typically involve gunmen ambushing military patrols in rural areas or using car bombs outside of police stations or military facilities in small towns. These attacks have resulted in some bystanders being killed. In recent decades, armed groups have also reportedly killed civilians or travellers in areas they control and where state presence is minimal. This seems to be driven by suspicion of people jeopardising their drug trafficking operations – guerrillas often kill civilians rather than capturing and interrogating them.

Bystanders at risk from drone attacks

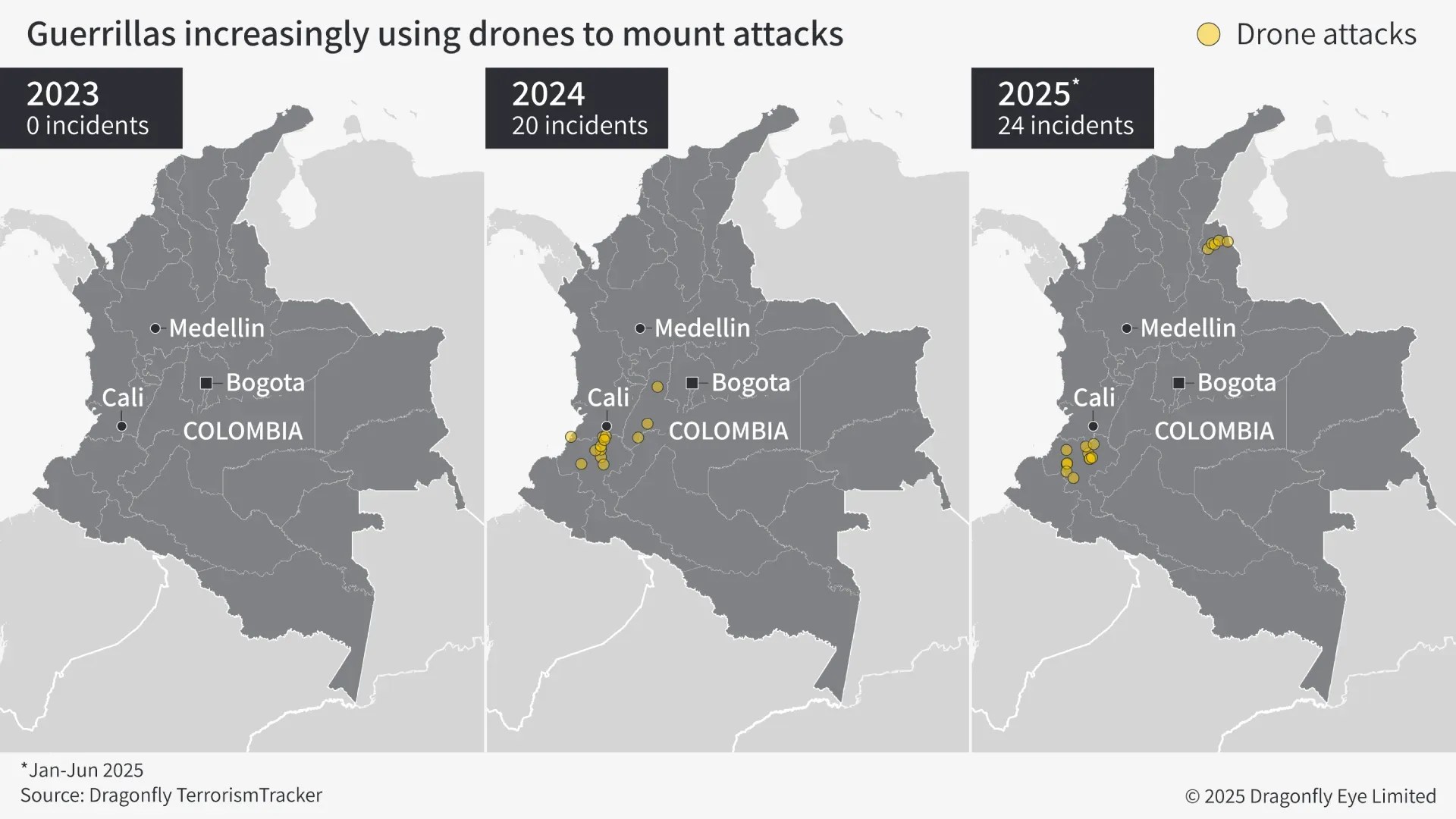

The proliferation of drones among guerrilla groups also means the already-high risk of bystanders being caught in a bombing in rural areas is likely to be elevated in the coming years. Since mid-2024, these groups have deployed cheap, modified commercial drones with release mechanisms to drop explosives on soldiers, military convoys and buildings. In particular, this is by the EMC and ELN in Cauca and Norte de Santander, respectively. While their primary targets are the security forces, civilians have also been injured or killed.

We assess that drones are likely to remain a key part of armed groups’ arsenals in the coming years. They are cheap and allow them to mount attacks with minimal risk to drone pilots. The Colombian military has occasionally used jamming devices to neutralise these drones. But their use is not widespread, and they pose the risk of drones – and their explosive payloads – falling on civilian sites.

Attacks in major cities likely to remain rare

Attacks by armed groups are likely to remain rare in major cities. Cali is the only major city where an armed group seems both capable of and intent on carrying out high-impact bombings. This year, the EMC has mounted several large attacks there, including a bombing on 21 August outside a military school that killed six civilians. While the group seems to view some civilian casualties as an acceptable consequence, the EMC seems focused on targeting the police or military in the city. Last year, it said harming civilians would be the ‘last thing’ it wanted.

At most, we anticipate sporadic, small-scale attacks in some major cities to intimidate – but not kill – the authorities and civilians. In a recent example of such an attack, the EMBF destroyed an electricity tower in Medellin with an explosive on 10 September. According to the mayor, the group was retaliating for military operations against it earlier that week. This attack seems to have been calculated to avoid casualties. Indeed, we assess such groups consider bombings in cities as counterproductive, as they would encourage an unwelcome response from the government.

‘This is an amended version of our SIAS report’

TOPSHOT – National Liberation Army ELN rebels of the Manuel Vazquez Castano northeastern war front stand guard at Catatumbo region, Colombia on March 8, 2025. (Photo by STRINGER / AFP) (Photo by STRINGER/AFP via Getty Images)