Disruptive energy shortages are unlikely this winter (November-March) in Europe

This assessment was issued to clients of Dragonfly’s Security Intelligence & Analysis Service (SIAS) on 11 September 2024.

- A deal allowing Russian pipeline gas to transit Ukraine to the continent is due to expire this December

- But the region is no longer critically dependent on Russian energy sources, including those countries previously most reliant on them

Energy supplies are likely to remain secure in Europe this winter. A deal allowing Russia to transport gas to Europe through Ukraine is due to expire this December. It seems all but certain that Ukraine will not renew it, and energy shortfalls leading to blackouts have previously been a concern for organisations in Europe. But even those countries most dependent on Russian gas imported through Ukraine – namely Austria, Slovakia, and Hungary – seem well-prepared to get supplies from elsewhere. And EU gas stocks are currently only one percentage point lower than they were this time last year, at around 92% of capacity.

Ukraine seems to rule out a new deal

Ukraine seems serious in its intention to let the gas transit deal expire. President Zelensky has said several times that Kyiv would not renew it; most recently, on 27 August, he said ‘nobody will extend the agreement with Russia’. And according to several statements throughout the year, the European Commission is seeking alternative measures to abandon its use of Russian gas, rather than negotiate with Russia to continue pipeline imports through Ukraine. Letting the deal expire is probably also a way for Ukraine to squeeze Russian revenues, in our view.

Europe’s dependence on gas transiting Ukraine diminished

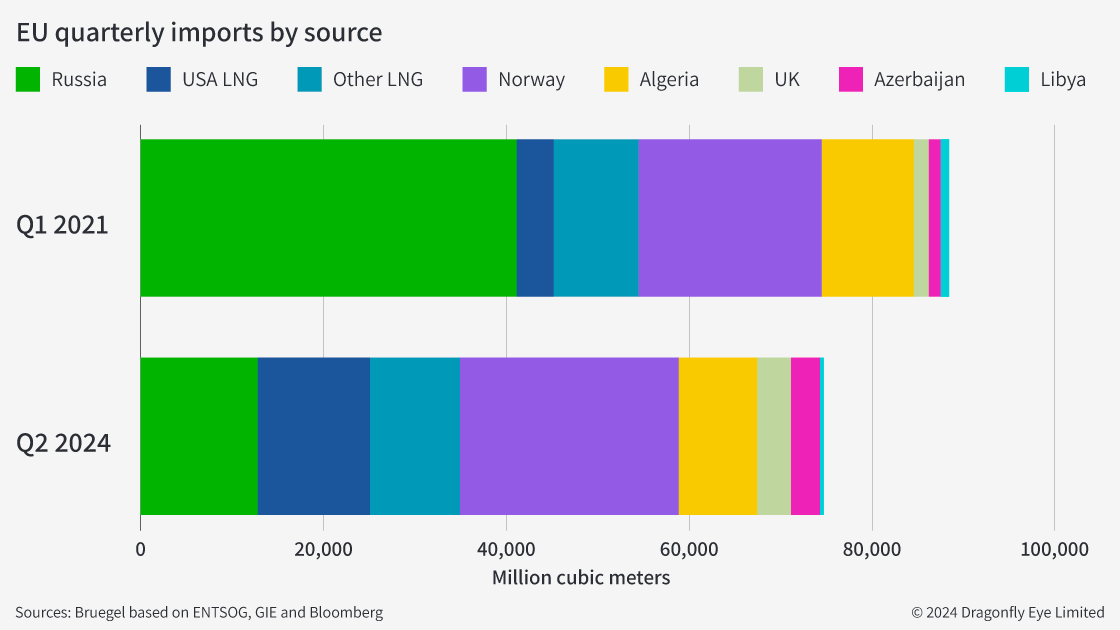

An end to Russian pipeline imports through Ukraine is unlikely to cause an energy security crisis in Europe. In recent years, EU countries have progressively turned to the more flexible option of liquefied natural gas (LNG). This particularly applies to gas from Russia. The EU has viewed Russia as an unreliable gas source, following the latter’s modulation of pipeline flows in 2022. The share of Russia’s pipeline gas in EU imports dropped from over 40% in 2021 to around 8% in 2023. For pipeline gas and LNG, Russia accounted for less than 15% of total EU gas imports in 2023, according to EU data.

That said, European countries have, at times, struggled to drastically and definitively reduce gas imports from Russia. For example, in the second quarter of this year (the latest data available) LNG imports from Russia to the EU overtook those from the US for the first time since 2022. This is despite EU efforts to the contrary; the EU increased its imports of US LNG from 18.9 bcm in 2021 to 56.2 bcm in 2023, with France being the main importer in Europe. The graphic compares the latest quarterly LNG import data with imports before Russia invaded Ukraine.

Parts of central Europe more exposed to gas reduction

Austria, Hungary and Slovakia seem prepared for a cutoff in supply from Russia. That is even though on the surface they look more exposed; Russian gas meets up to 95%, 70-80%, and 80-90% of their total gas demand, respectively. The Austrian energy regulator earlier this month said it had already factored in a total suspension of Russian gas into its winter plans for each year until early 2026. And the Austrian authorities have proven capable of reducing demand when needed; local media outlets have reported a reduction in demand of 23% since Russia invaded Ukraine, well above the EU demand reduction target of 15%.

Slovakia and Hungary also seem able to tackle a cutoff in gas from Russia. Slovakia previously depended on Gazprom for all of its gas imports, but the prime minister told the local press in August that he would do ‘everything politically necessary’ to use gas from Azerbaijan instead of Russia. And Hungary, which only imports around 20% of the gas it buys from Russia through Ukraine, last year signed new contracts with Turkiye to help bolster gas supplies; these imports began in April.

It appears feasible for European countries to rely on alternative gas supplies, including from Azerbaijan. That country’s president in July said ‘we are trying to do everything’ to meet a commitment that would see it double current annual exports to the EU by 2027. But progress on the project seems stalled, probably because of a lack of funding to upgrade pipelines. Azerbaijani President Aliyev said this was down to European banks in recent years scaling back loans for fossil fuel projects due to climate policies.

Regardless of climate targets, the EU is likely to prioritise securing stable energy supplies, particularly when these seem at risk. For example, the EU’s fossil fuel subsidies in 2022 (when Russia invaded Ukraine and began to modulate gas supplies) were double the average of the previous seven years.

Some options for Europe to get Russian gas

Moscow seems keen to continue shipping gas to the region by any means possible. This is not least due to Gazprom’s vast revenue losses; it is cut off from most of its European market. A spokesperson for the Kremlin earlier this month said they would use alternative routes, namely Turkiye, to continue to serve European markets in the event Kyiv no longer allows Russian gas to transit Ukraine. But this is likely to be a relatively slow-moving solution; Moscow first proposed the idea in 2022, yet negotiations around a project roadmap are still ongoing.

Image: Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) storage tanks are seen at the Grain LNG import terminal near Grain, Isle of Grain, southeast England, on 21 September 2021. Photo by Daniel Leal/AFP via Getty Images.