Operating in and travelling to Libya in 2025 will very probably remain difficult in the coming year

This assessment was issued to clients of Dragonfly’s Security Intelligence & Analysis Service (SIAS) on 28 November 2024.

- Despite fragile stability holding in recent years, structural weaknesses remain – meaning that a months-long bout of localised clashes or a resumption of countrywide armed fighting remains probable

- In our analysis, such a security crisis would most probably be triggered by instability in the Tripoli government

There is little to suggest that businesses operating in and travelling to Libya next year will be able to ease their mitigation of security risks. This is despite the relatively predictable environment over the past few years which has meant several foreign companies have resumed operations and travel there. Armed fighting between rival militias in the west has been largely contained. And the tacit cooperation over oil production between opposing authorities in the east and west of the country seems to be holding. Still, structural weaknesses remain, meaning a months-long bout of localised fighting, or a resumption of countrywide armed fighting, remains probable over the coming years.

Clients have asked us what they can monitor to anticipate such fighting. In our analysis, any political or security crisis (especially in 2025) is very likely to be triggered by instability in the Tripoli government. This is because the Tripoli Government of National Unity (GNU) led by prime minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah appears weakened, amid public and local militia opposition. And because General Haftar of the Libyan National Army (LNA) in the east has tended to seize on serious instability in the GNU to challenge it.

East-west relations teeter on the brink

Several international energy companies have since October resumed onshore oil exploration after a hiatus of at least ten years. This is as the precarious status quo between rival authorities in the east and west of the country seems to still be holding. Haftar and Dbeibah have in the past few years continued to demonstrate their willingness to resolve disagreements politically rather than militarily. The latest example is the resumption of oil production after a central bank dispute halved oil output this autumn. Oil production continues to incentivise both sides, including allied militias, to maintain stability.

Animosity between the east and west remains deep-rooted, with both sides claiming to be the rightful governing force in the country. These tensions mean a sustained armed conflict between the two sides is plausible over the next year. Both sides continue to engage in brinkmanship, attempting to wrest influence from each other rather than working towards unity. Further disputes are therefore all but certain to arise over issues such as senior appointments for state institutions and budget allocations. And with no formal ways of resolving these, there is a reasonable possibility that either side would eventually resort to violence.

Western Libya: anti-government sentiment and political violence on the rise

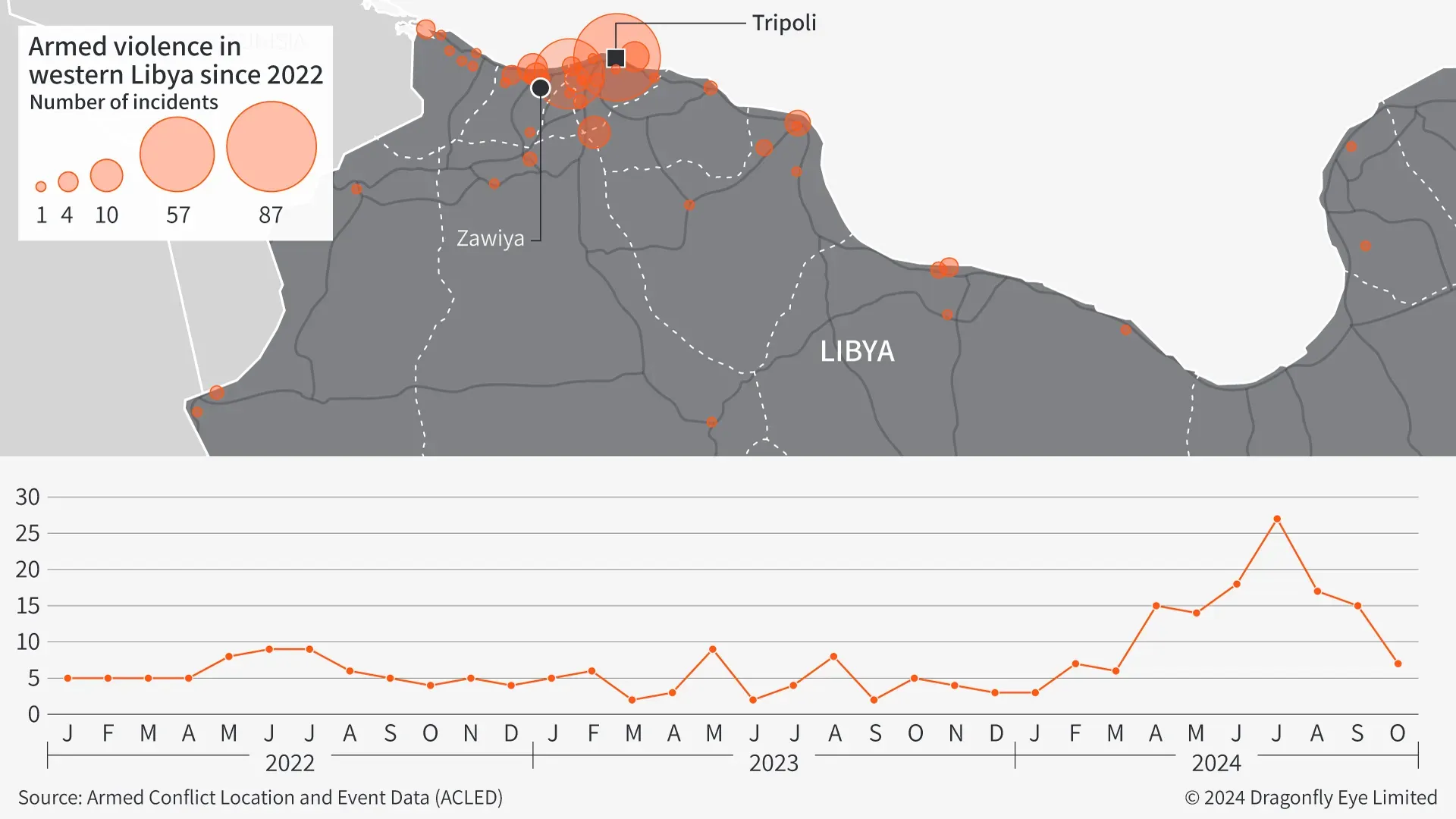

Given all this, the main development we are motoring for is the collapse of the GNU, which is probable over the coming years. This is for two main reasons. First, anti-government sentiment seems to be growing. Based on data from our partner Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED), protests in western Libya have doubled this year (132) compared with the same timeframe last year (65). These were mostly over living conditions, insecurity and corruption, sometimes calling for a unified government. Instead of addressing protest drivers, Dbeibah has often responded with force. This provides an opportunity for militias to side with protesters.

Second, the GNU’s influence over militias appears to be waning. The GNU has for years struggled to maintain security, and a weaker government means that clashes will last longer. Such clashes over control of trade and smuggling hubs are already frequent. Rival groups have fought with each other nearly twice as much in 2024 (129) so far as in the whole of 2022 (70) and 2023 (67), based on ACLED data. Most of these skirmishes took place in Zawiya and Tripoli in northwestern Libya. According to ACLED, the number of active conflict actors in July reached 65, the highest level of armed group fragmentation since December 2019 – a time of civil war.

Tripoli the main stability faultline

The collapse of the GNU carries a very high chance of sustained and widespread armed fighting across the country. It would also cause severe disruption to oil production, in our assessment. In the west, widespread armed fighting is a potential precursor and consequence of any signs that the GNU is on the verge of collapse. This is because many of the groups that are aligned with the GNU do so out of convenience and access to state resources. The collapse of the GNU would present an opportunity for powerful west-based militias to expand their influence over state resources.

There would also be a high risk of the fragile peace between the east and west faltering. First, many west-based militias have publicly criticised the GNU for its dealings with General Haftar; many groups in Tripoli accuse the LNA of war crimes during the civil war. The collapse of the GNU would empower west-based groups to disrupt oil production and revenue transfers to the east. Second, it is highly plausible that any perceived weakness in the west would motivate General Haftar to encroach on Tripoli’s stability – both by enforcing oil blockades in the east, but also militarily; in 2020 General Haftar led a failed offensive against Tripoli.

We have identified the following triggers, indicators and impacts of a months-long bout of armed clashes in western Libya:

Triggers:

- The GNU excludes a prominent group from access to previously held resources by reappointing coveted positions

- GNU security forces kill dozens of protesters during widespread anti-government protests, prompting militias to step in

- Months-long oil sector shutdowns resulting from a dispute between the east- and west-based authorities prompt west-based militias to confront GNU forces

- An extreme weather event kills several dozen people or more and causes major damage due to a governance failure, prompting widespread protests backed by militia leaders

Indicators:

- Incidents of political violence spread geographically, or intensify in areas where there was previously less violence, such as Garyan and Misrata, and become more frequent

- West-based armed groups form new alliances that oppose the GNU

- Recurrent large, more widespread and violent political demonstrations

- The central bank stops payments to one or both of the east- and west-based authorities

- One of Dbeibah’s foreign backers (mainly Turkiye, Qatar and Italy) sides with a high-profile armed group leader, for instance by making trade or security arrangements directly with them and bypassing the GNU

- The GNU significantly increases weapons imports, such as drones, from Turkiye

Impacts:

- Fighting would mostly take place near the coastline, with sporadic attacks and confrontations across inland western Libya, such as in Qaryat and at oil infrastructure

- Overall safety and security would deteriorate, and overland travel within and between cities would quickly become difficult due to roadblocks

- Foreign governments would call for and set up evacuations for their citizens

- Armed groups would almost certainly seek to prevent oil from being exported if any production remains possible

- East-based LNA forces would probably seek to increase their influence in the west, carrying with it a very high risk of armed clashes between east and west-affiliated forces countrywide

We have not seen anything to suggest that such a scenario is imminent. However, militia posturing and loyalties in western Libya often shift fast, so a crisis there can occur with little to notice. The most reliable indicator of the situation worsening is armed clashes in Tripoli lasting more than a week; the GNU has in the past few years effectively contained these, limiting them to a few days at most.

Image: An Aerial View of Ottoman Clock Tower or Burj Assa,a in the Old City (Medina) of Tripoli, Libya, on 14 March 2022; Photo by Bashar Shglila via Getty Images.