Record-high levels of drug production and consumption globally are highly likely to drive corruption, reputational, and safety risks for businesses in Latin America and Mexico in the coming years.

This assessment was issued to clients of Dragonfly’s Security Intelligence & Analysis Service (SIAS) on 13 December 2023.

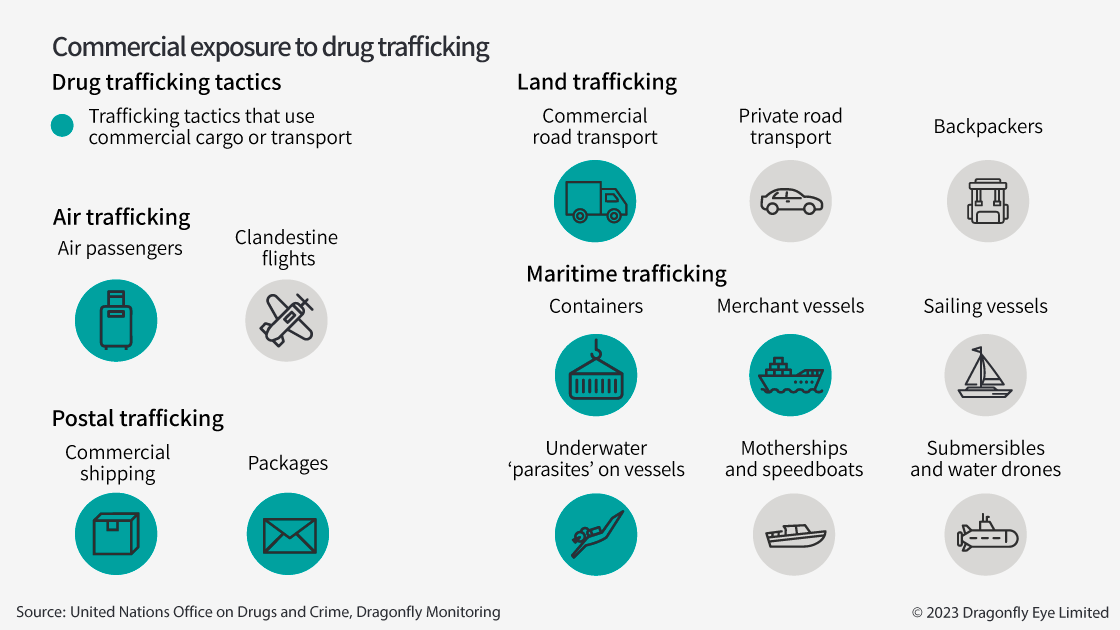

- Criminals are highly likely to attempt to conceal drug shipments in commercial cargo in Latin America in the coming years

- In recent years, traffickers have developed highly complex concealment methods to evade the authorities

- The authorities are unlikely to curb trafficking rates or resulting violence between rivals; global demand for drugs from South America remains strong

Commercial cargo is becoming an attractive target for traffickers seeking to conceal drug shipments and they have developed innovative ways to do so. Competition between these groups over drug smuggling routes is also likely to drive high rates of gang violence in port cities and along trafficking routes, particularly in Colima (Mexico), western Ecuador and Limon (Costa Rica).

Production and consumption at record high levels

Drug trafficking remains incredibly lucrative, as drug production and consumption are at record-high levels, in particular for cocaine. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has said this year that levels of coca production in Colombia are the highest since it began monitoring in 2001. UNODC data also shows it is increasing in Bolivia and Peru as well, likely due to the increasing use of trafficking routes in the south of the continent. Production in both countries had slumped in the mid-2010s. The UNODC also said there is a ‘rising prevalence’ of cocaine use globally, as well as a greater demand for cocaine due to population growth.

Criminals have shown resilience to previous attempts to curb trafficking. The huge profits gained from trafficking have almost certainly motivated them to innovate and find creative ways to avoid detection. Governments in the region and globally have also not developed effective policies to combat trafficking, while regional cooperation and intelligence sharing appear to be minimal. For example, the judiciary in Costa Rica recently announced an investigation into an alleged government deal with drug cartels to curb violence in exchange for not obstructing trafficking operations.

Traffickers adapting smuggling methods

Concealment in legal cargo is becoming an increasingly attractive way to conceal drugs, according to the UNODC. Rather than risk detection by concealing drugs in private, irregular transport, traffickers have sought to hide their activities within the everyday global flow of imports and exports. This involves creative measures to avoid detection and the use of insiders, such as port workers, shipping crew or customs officials, both in Latin America and Mexico and at destinations, mainly the US and Europe.

The most common way to conceal drugs in products is through low-cost goods shipments for which there is poor security. Agricultural goods appear to be the most common legal cargo targeted; as the region’s biggest export, there are regular and large volumes of transnational shipments for traffickers to exploit. Criminals have reportedly set up front companies to completely control the operation. In September, the Ecuadorian government suspended the export licences of around 50 banana companies for this reason.

Illicit drug cargo is not always immediately detectable. Drug traffickers are using chemical camouflaging, based on police discoveries of laboratories across Europe. This involves using complex chemical processes to hide cocaine by infusing it onto legal cargo; the UNODC said cocaine has been discovered in ‘beeswax, plastics, herbs, charcoal and various liquids’. At its destination, the drug is then separated. In one example, police in Cartagena, Colombia, reportedly seized almost 20,000 coconuts filled with ‘liquid cocaine’ last year.

Low-cost goods are likely to remain the most common target, but there is a high chance criminals will seek to exploit any cargo leaving the region. Latin America and Mexico’s other primary exports, (such as minerals and petroleum) are not generally exported to the largest drug markets, which remain the US and Europe. And security measures for such higher-cost exports also probably deter criminals. But traffickers have consistently shown a willingness and ability to innovate, meaning no type of cargo is off-limits.

Concealment inside shipments, rather than products, appears to be mostly opportunistic. Criminals reportedly use legal shipments, particularly shipping containers going to the US and Europe, without tampering with legal cargo. Insiders, such as customs officials, port workers and drivers appear to be essential to this. They facilitate circumvention of security measures by breaking open seals on containers and replacing them with replicas, or unloading drug shipments on vessels at sea, rather than in heavily securitised ports. Most accomplices appear to have been paid, rather than threatened, based on our monitoring of regional news outlets.

Concealment inside shipments, rather than products, appears to be mostly opportunistic. Criminals reportedly use legal shipments, particularly shipping containers going to the US and Europe, without tampering with legal cargo. Insiders, such as customs officials, port workers and drivers appear to be essential to this. They facilitate circumvention of security measures by breaking open seals on containers and replacing them with replicas, or unloading drug shipments on vessels at sea, rather than in heavily securitised ports. Most accomplices appear to have been paid, rather than threatened, based on our monitoring of regional news outlets.

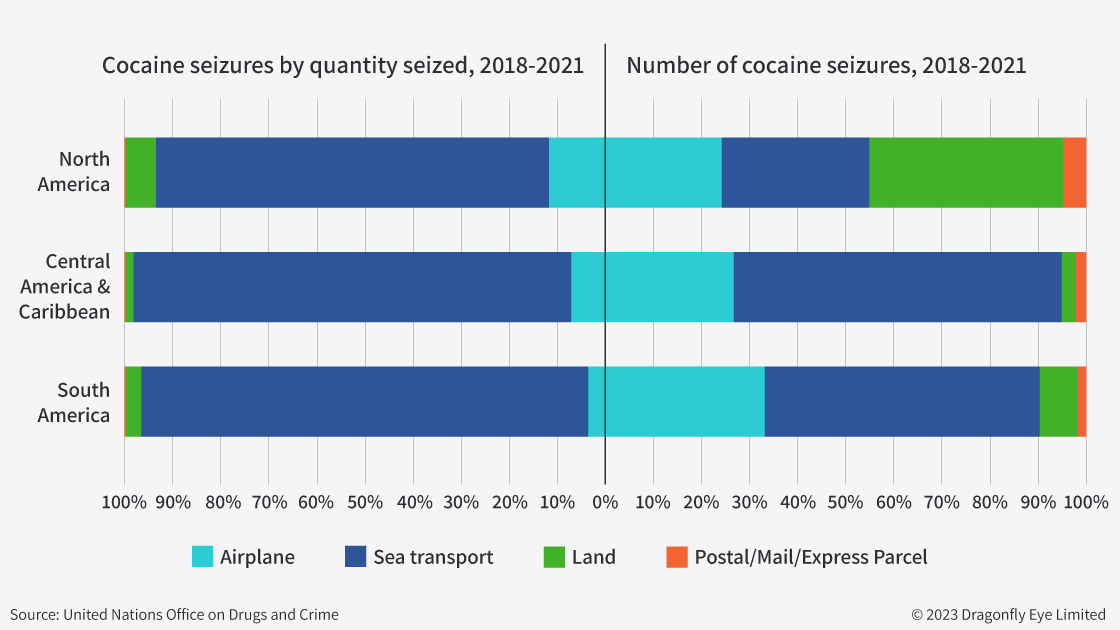

Police drug seizure data suggests that maritime trafficking remains the most prevalent. As shown in the graphic above, although there are frequent air and land seizures across the region, the quantity of cocaine transported is significantly larger by sea. Many maritime methods, such as the use of private vessels, do not seem to disrupt commercial operations. But according to the UNODC, traffickers are using tactics that do affect those operations, such as shipping containers. This includes concealing drugs ‘in the structure of a container’. Other tactics include scuba divers attaching underwater ‘parasite’ packages to the hull of vessels before a ship departs.

Police drug seizure data suggests that maritime trafficking remains the most prevalent. As shown in the graphic above, although there are frequent air and land seizures across the region, the quantity of cocaine transported is significantly larger by sea. Many maritime methods, such as the use of private vessels, do not seem to disrupt commercial operations. But according to the UNODC, traffickers are using tactics that do affect those operations, such as shipping containers. This includes concealing drugs ‘in the structure of a container’. Other tactics include scuba divers attaching underwater ‘parasite’ packages to the hull of vessels before a ship departs.

Disruption and delays for business operations

Companies are likely to be unaware their cargo has been used for drug trafficking. But efforts to reduce this, such as recently announced plans in Ecuador and Brazil to militarise major airports and ports, will probably expose international businesses to reputational risks and loss of cargo. That is even though these governments have not issued warnings about delays; most governments appear intent on avoiding operational disruption to cargo shipments.

But significant drug discoveries are likely to cause disruption. The US authorities reportedly seized a container ship in 2019 with 20 tons of cocaine hidden in containers of wine and nuts. Although the shipping company said other cargo was diverted to other vessels without major delays, the US authorities only released the ship 12 days later when the company paid a $50m bail. They had initially threatened to hold it permanently. In our analysis, the effect of searches and discoveries is likely to be greatest for businesses moving perishable goods.

Drug trafficking groups seeking alternative routes

Security measures have also led trafficking groups to divert their activity to alternative routes. This was most notable during the Covid-19 pandemic, when restrictions at land borders across the region led to an increase in the use of clandestine air and maritime routes, according to the UNODC. Traffickers often use what the UNODC has called the ‘path of least resistance’ to avoid law enforcement, even if it involves longer distances. For security managers looking at their organisation’s supply chains, this creates ever-evolving challenges and a geographically unpredictable risk.

Drug trafficking is likely to sustain high violent crime rates regionwide, particularly in port cities. This week the Australian government advised its citizens to reconsider travel to Guayaquil due to gang violence. Other affected cities include Barranquilla, Cartagena (Colombia), Limon (Costa Rica), Puerto Bolivar (Ecuador) and Manzanillo (Mexico). Most violence does not directly affect businesses – criminals typically target rivals or their collaborators. But gangs can cause business disruption; in September, 400 containers were reportedly moved from Puerto Bolivar to a different port due to extortion attempts.

Image: Aerial View of container ship terminal in Hong Kong, China. Photo by Nikada via Getty Images.