We assess that there is a high chance of minor skirmishes between India and China in border regions such as Ladakh.

This assessment was issued to clients of Dragonfly’s Security Intelligence & Analysis Service (SIAS) on 28 August 2024.

- Border talks have remained stalled over the past year, although both sides agreed to de-escalate their conflict during meetings in July

- A wider military escalation is unlikely as India and China do not appear intent on engaging in conflict and face significant capacity constraints

A territorial dispute between India and China will probably drive sporadic border clashes between the two sides into 2025. The situation at the border remains fluid; both sides deployed thousands of additional soldiers there following a fatal clash in the Ladakh region in 2020. Still, there is a low chance of such skirmishes devolving into a full-fledged war, in our assessment. India and China do not appear intent on large-scale conflict. Various think tanks and research studies suggest they face capacity gaps limiting their ability to engage in such hostilities over the coming year.

Longstanding instability along the border continues

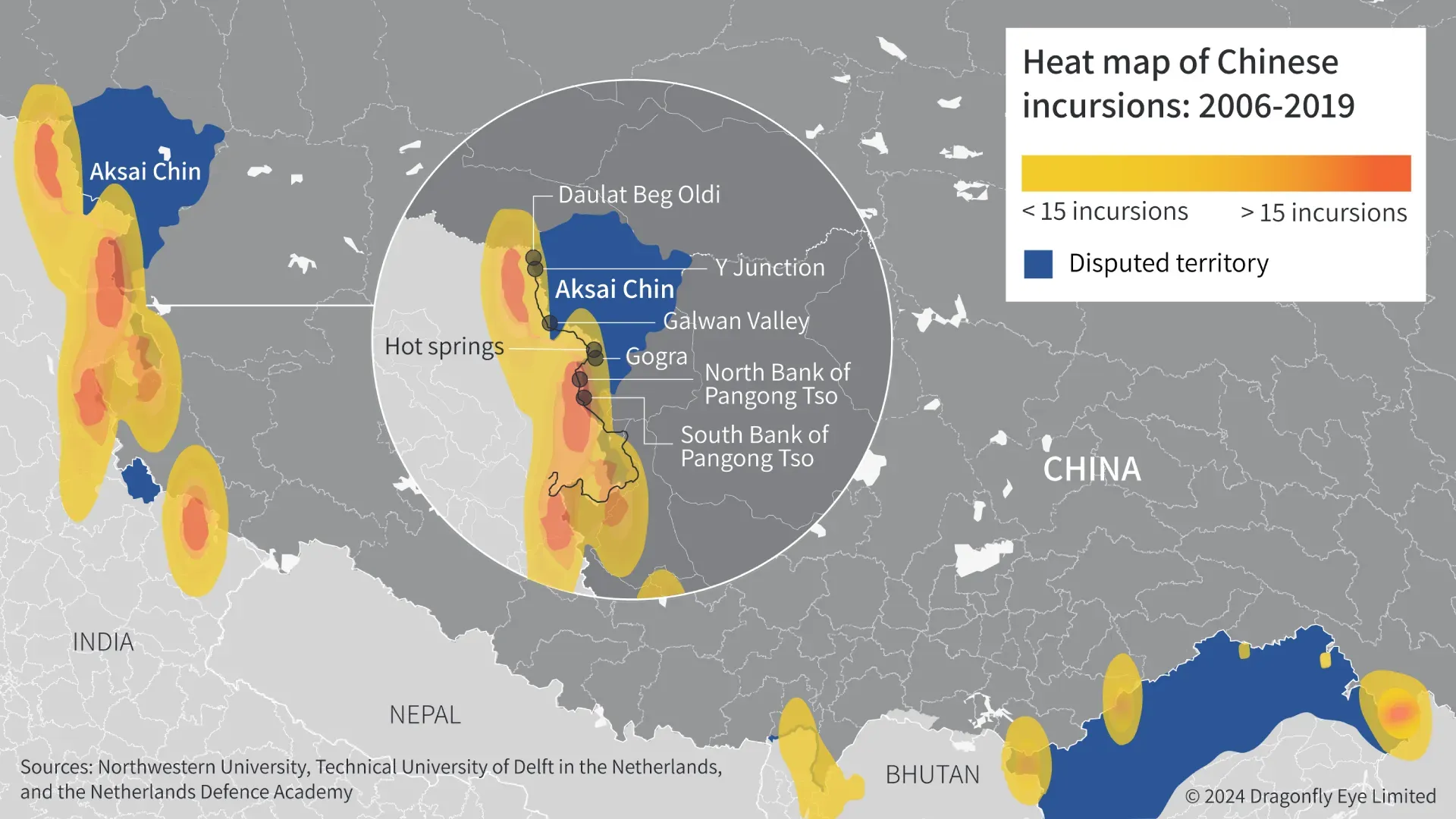

The frequency of Chinese incursions into India across the Line of Actual Control (LAC) has risen over the last decade or so. According to Indian government data, there have been hundreds of ‘border incidents’, comprising incursions as well as skirmishes and standoffs between opposing troops over the past two decades. The number of these has increased steadily from 228 incidents in 2010 to 663 in 2019. And in 2020, a clash between the two sides in Galwan valley in India’s Ladakh region led to the deaths of dozens of soldiers.

The Indian government has stopped releasing data on the number of border incidents after the clash in 2020. But as far as we can determine this trend has continued. Both sides have also moved tens of thousands of troops to positions along the boundary over the past few years. There have been no further fatal clashes since then; patrols rarely carry firearms. But limited skirmishes occur every few months.

The exact frequency of these incidents is difficult to gauge; however, the two sides have engaged in 21 rounds of military-level talks over the past four years, according to local media reports. And publicly available images and videos suggest there have been several incursions and clashes that have not been publicised by India or China.

That said, both China and India appear intent on de-escalating tensions along the border and preventing a major conflict. In addition to the ongoing talks, the two sides have established additional military hotlines and buffer zones in conflict areas over the past few years and repeatedly engaged in conciliatory rhetoric. Most recently, the Indian and Chinese foreign ministers agreed to pursue ‘complete disengagement at the earliest’ during one of their meetings in July.

Low likelihood of resolution to the territorial disagreements

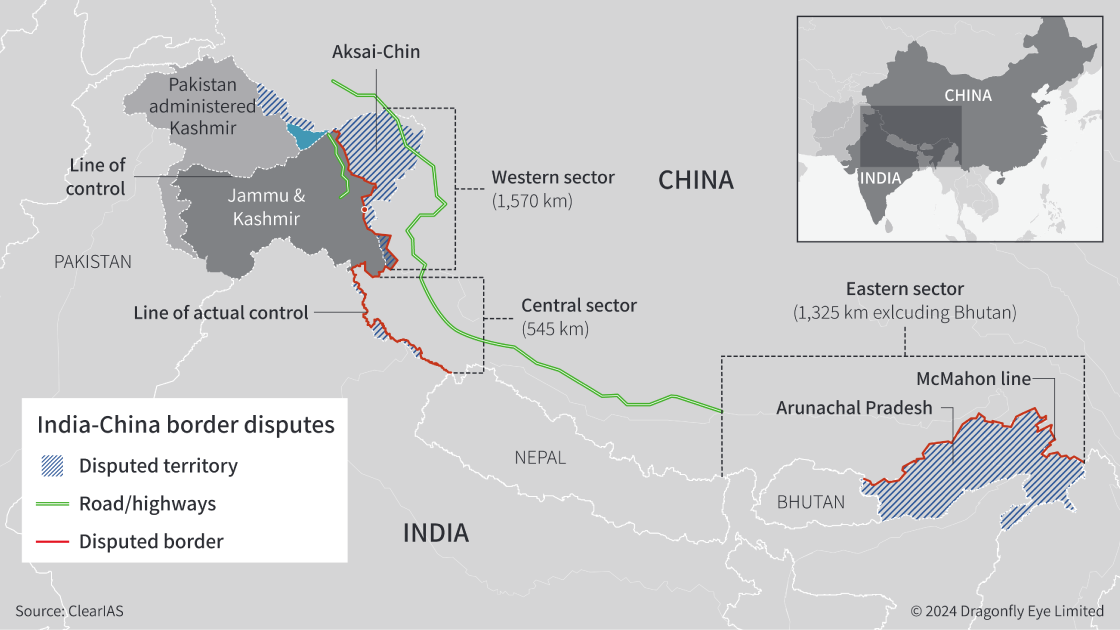

There is little to suggest that talks will lead to a sustainable agreement anytime soon. So far, negotiations have focused only on the Ladakh region (western sector) and do not cover areas in the eastern sector such as Arunachal Pradesh (see below map). And they are also reportedly spearheaded by military commanders, meaning the talks are probably covering tactical details rather than a broader resolution.

We doubt India will offer territorial concessions to advance negotiations. Local media reports imply that China does want to reset its wider relationship with India. But India has so far refused to normalise relations unless China vacates occupied areas in core disputed regions such as Depsang in Ladakh. These are of strategic importance to India, based on statements by Indian military officials. Beijing has for now refused these demands. As a result, talks have reached an impasse, according to local media reports in the past few months quoting key government officials.

Outlook for border clashes into 2025

We assess that further clashes between India and China are probable every few months in the coming year. Border altercations are particularly likely in areas in Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim in the eastern sector and Ladakh in the western sector in the coming year. This is where clashes have occurred previously, especially around flashpoints like Demchok and Depsang (in the west) and Naku La and Tawang (in the east). Such skirmishes tend to occur as part of standoffs between rival troops, or when opposing patrols come across each other.

Any skirmishes will probably be short-lived and stop short of troops using firearms. Most reported incidents since 2020 consisted of soldiers engaging in violent brawls (such as throwing rocks and using sticks, clubs, spikes, and other melee weapons) or at most firing shots in the air. Both sides have largely kept to a 1996 agreement to not shoot live rounds at each other at the LAC. In our analysis, this is because both seem to lack the appetite for military conflict. And infrastructural constraints – not least roads and air bases – faced by China in the region would also probably discourage it from engaging in prolonged fighting there.

The likelihood of inadvertent escalation is also low, in our assessment. Moreover, the buffer zones and other deconfliction mechanisms will probably help contain any escalation that would be prompted by casualties or other triggers such as a decision by either side to lay claim to previously uncontested areas. Our interstate conflict risk level for both countries is high.

Image: Activists of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) stand in line as they prepare to burn an effigy of Chinese President Xi Jinping during an anti-China protest in Siliguri. India and China held top level talks on June 17 to “cool down the situation”, Beijing said, after a violent border brawl that left at least 20 Indian soldiers dead, on 17 June 2020. Photo by Diptendu Dutta/AFP via Getty Images.