Most anti-US sentiment this year will probably manifest as online calls for boycotts, small protests at diplomatic missions, and isolated verbal harassment

This assessment was issued to clients of Dragonfly’s Security Intelligence & Analysis Service (SIAS) on 23 April 2025.

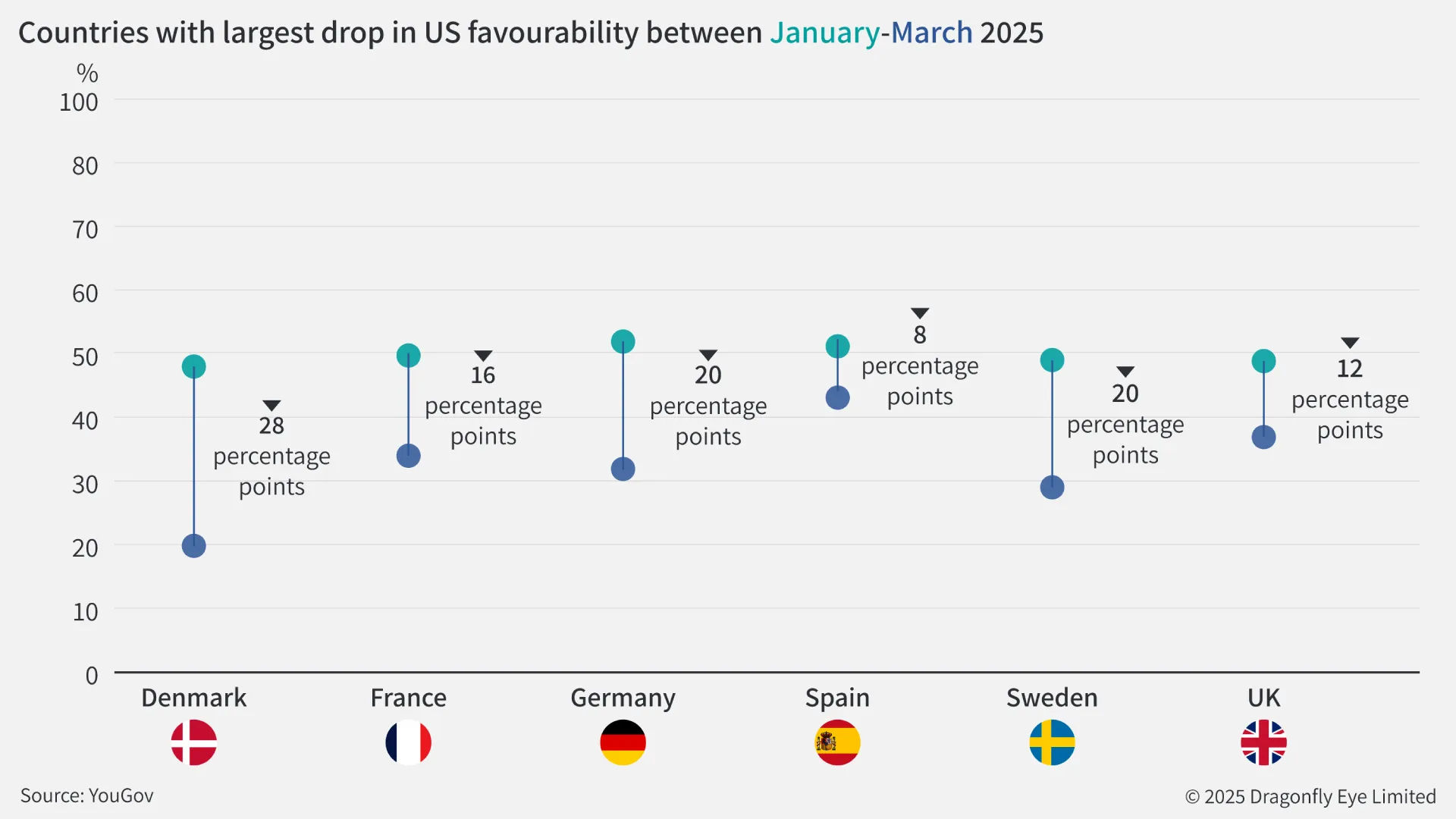

- Recent polls suggest that US favourability in Europe has fallen significantly in several countries since President Trump took office in January

- Coordinated or widespread violence against US companies, business leaders and travellers remains unlikely

Anti-US sentiment appears to be rising in Europe, largely driven by President Trump’s policies and rhetoric. In recent weeks, hundreds of people have protested against US tariffs, and assailants damaged Tesla and Trump-linked sites in Germany, France and the UK. But we do not assess that these isolated incidents indicate a turn towards organised violence against US businesses or travellers more broadly. Most of this souring of sentiment will probably manifest as online calls to boycott US goods, isolated protests at US diplomatic missions, and infrequent verbal street harassment.

Trump driving anti-US sentiment, especially in northwestern Europe

The trend appears to be driven by President Trump’s policies and rhetoric towards several European leaders and countries. Several local polls and research from social institutes in the region point to a sharp drop in favourability towards the US in many countries since he took office on 20 January. Between January and March, the largest drops in public favourability were in Denmark (48% to 20%), Sweden (49% to 29%), Germany (52% to 32%), France (50% to 34%), the UK (49% to 37%) and Spain (51% to 43%).

Denmark has experienced the largest fall in favorability. This shift has very probably been driven by Trump’s repeated expression of interest in acquiring Greenland (an autonomous Danish territory), and his repeated threats of coercion – assumed to be economic, but without ruling out the use of military force. In a sign of this, in early April, the Danish foreign minister said in a video on social media that he did not appreciate the recent ‘tone’ and ‘approach’ of the US on Greenland.

In other countries, the shift appears to be driven by a combination of several factors largely linked to President Trump. These include his trade policies, a perception of waning US commitment to NATO and to European security, a weakening of support for Ukraine, a perception that Trump admires President Putin of Russia, and foreign policy statements directed towards European leaders. These have included comments on absorbing Greenland or Europe not showing ‘gratitude’ to the US.

Calls for boycotts and isolated protests

Most anti-US sentiment this year will probably manifest as calls to boycott US products. Up to ‘70% of Swedes’ either avoid or have considered avoiding US products, according to a survey published in a Swedish media outlet in March. We have also seen boycott calls in anti-Trump social media groups in Nordic countries, Germany, France, the UK and the Netherlands. These seem unlikely to turn into major boycotts; most groups only have a few thousand members, and we have not seen remarks from officials supporting them. High-profile firms associated with Trump are most at risk of boycotts; Tesla vehicle sales have fallen regionwide since January.

There are also likely to be some small and sporadic protests. In the last few weeks, these have occurred in Finland, Norway, Denmark, Germany, France, the Netherlands and the UK, many near US diplomatic missions. But these only drew a few hundred people each and did not lead to violence. Many also took place at Tesla sites or solely referenced President Trump, suggesting that they are often directed at the US leader personally or brands linked to him. A state visit by Trump, such as the one planned to the UK later this year, would probably increase the size and frequency of protests.

Isolated verbal street harassment of Americans is reasonably likely in Europe this year. In February, an American tourist in Copenhagen said they were told to ‘go home’ after locals heard their accent in a bar. And in March, a US student was reportedly heckled in Berlin near a protest against US tariffs. Some US tourists have said on travel forums that they tell locals that they are Canadian when in Europe, to avoid such incidents. But based on recent press reports, these will probably remain sporadic and unorganised, occurring opportunistically at busy locations, like bars or protests.

In countries such as Serbia, where US favourability is already low (under 20% according to a recent Gallup poll), anti-US protests, informal boycotts of US goods, and sporadic verbal harassment also remain probable. These are often conducted by right-wing groups and tied to the NATO bombing of Serbia in 1999, as well as public perceptions of US support for Kosovo. Last year, a passerby reportedly shouted insults at the US ambassador. And in March, a few thousand right-wing activists protested a US-funded luxury development in Belgrade, but only minor disruption was reported.

Organised or widespread violence against Americans unlikely

Widespread or coordinated violence against US businesses or travellers remains unlikely in Europe. In recent weeks, far-left groups have set fire to and vandalised Tesla sites in France, Germany, Italy and the UK, while pro-Palestine activists defaced a Trump-owned golf course in Scotland. But these sites appear to have been targeted over links to the US administration and do not indicate a turn towards organised violence against US firms or citizens more broadly. We have not seen any reports of, or calls for, attacks on US firms or citizens, or warnings from governments.

We have also not identified a rise in threats to US business leaders in Europe recently. Far-right and far-left extremists, as well as conspiracy theorists have all made generic threats of violence against US corporate heads in recent months. This is especially against those in financial, energy, technology, health and defence firms. But these are common throughout the year on the online channels we monitor and do not appear to be associated with the recent apparent drop in favourability of the US. Such threats very rarely result in attacks.

We have identified several indicators that would probably generate a rise in anti-US sentiment in Europe, and with it the risk of a broadening of hostility and even violence towards American citizens more generally. And while these might increase the likelihood of violent incidents, we still do not anticipate such cases to become widespread across the region. In no particular order, these are:

- A significant push or attempt by the Trump administration to annex Greenland, or to deploy US forces to Gaza

- A major increase in US tariffs on European goods, and the descent into a US-Europe trade war

- A large and very sudden reduction of US military presence in Europe

- Rhetoric or actions by US officials perceived by the public as interference in European politics, such as tying trade agreements to anti-discrimination rules

- The Trump administration bringing a diplomatic resolution to the Russia-Ukraine war that is perceived by Europeans to be on Russia’s terms

Image: A woman holds an EU flag as people take part in an anti-government protest organized by political activists of the Peace in Ukraine organization under the slogan “No to the Russian Law”, against a planned law intended to complicate the work of non-governmental organizations on April 24, 2025, in Bratislava, Slovakia. (Photo by TOMAS BENEDIKOVIC / AFP) (Photo by TOMAS BENEDIKOVIC/AFP via Getty Images)