Farmers protesting in Europe are likely to continue bottlenecking supply chains over the coming year. Such developments are particularly likely in the lead-up to European Parliament elections from 6-9 June.

This assessment was issued to clients of Dragonfly’s Security Intelligence & Analysis Service (SIAS) on 06 February 2024.

- Protests across Europe by farmers are likely to continue at least until June when EU parliamentary elections are due

- This is because farmers are seeking concessions ahead of the vote

- Border crossings, motorway junctions and, to a lesser extent, access to ports and airports are likely to be impeded

It is clear that farmers across the region, despite their differing grievances, are taking inspiration from similar protests elsewhere and holding their own roadblocks. These are likely to continue to mainly involve blocking motorway junctions, main roads in major cities and, in rare cases, airport access roads, impacting overland travel for both public and business (supply chain) vehicles.

Agricultural and climate policies angering farmers

Farmers holding these protests seem to have two main grievances. The first is EU and national policies they perceive to be negatively affecting the sector. Those include the removal of agricultural subsidies and tax cuts, and perceived overregulation linked to climate targets. The second is the effect of the war in Ukraine on the sector; the price of fertiliser and energy has significantly increased farmers’ operating costs. According to the World Bank, fertiliser prices rose by 30% between January and May 2022, having already increased significantly after the Covid-19 pandemic.

Large-scale protests have taken place so far in the following countries in the last 12 months (those where we expect further large, disruptive protests this year are in bold):

- Austria

- Belgium

- Bulgaria

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- Ireland

- Italy

- Lithuania

- Netherlands

- Poland

- Portugal

- Romania

- Slovakia

- Spain

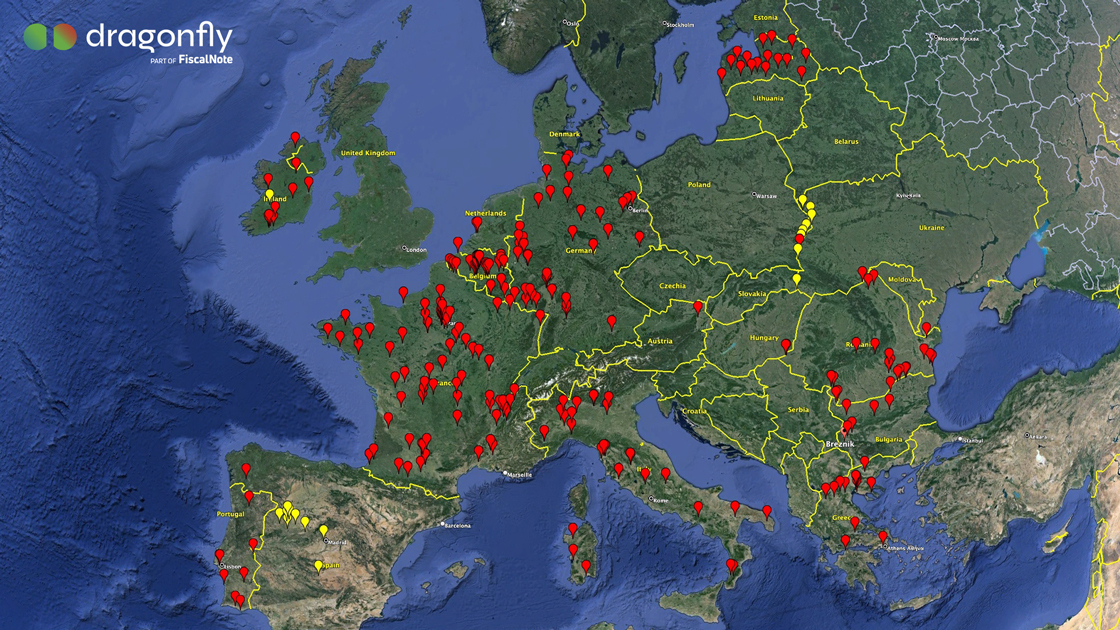

In the interactive map above, we have used open-source reports to collate location details of plans for future protests as well as those of past protests. This is to give an overview of the locations farmers are choosing to target with disruption and where this is likely to take place during future demonstrations. There are other countries where significant protests have not yet occurred, but seem more likely than not. These include:

- Albania. Farmers have already held small protests involving a few dozen people against a perceived lack of government support for the sector; based on the importance of agriculture for the country (around 19% of GDP) it seems likely that these will expand in location and level of participation.

- Denmark. Farmers mobilised in 2020 against controversial policies affecting the sector, and they do not appear immune to the stress the sector is experiencing elsewhere in the region.

We do not anticipate significant farmers protests – at least for now – nationwide in the UK. Farmers there do not seem to be as interested in holding protests; Scotland’s biggest farmers’ union has said it will not call on members to mobilise. While there was a protest of several hundred farmers in rural Wales last week, this was at a market and did not seem to cause major disruption. In our analysis, the lack of motivation among UK farmers is probably because they are not as directly affected by EU policies, and they control larger divisions of farmland compared with EU farmers (and so have less precarious economic conditions).

Disruption until at least June

We forecast that farmers will persist in holding protests until at least the first week of June. This is when Ukraine’s duty-free access to the EU is due to expire (4 June), and when EU Parliament elections will take place (5-9 June). The grievances of farmers in these countries focus particularly on EU agricultural policies, so participants will probably continue to use the protests as a way to either gain concessions ahead of the vote, or to encourage votes for new MEPs sympathetic to their cause.

National governments are likely to make at least partial concessions in most instances. There are already signs that many are open to doing so, such as in France and Germany. But these are unlikely to completely placate farmers. This is not least because farmers’ unions do not appear to have full control over their members. In an example of this, according to French media, many protesters in France late last week continued roadblocks even after major unions called for an end to them.

The role of right-wing populist and far-right groups in the movement is another reason why protests are likely to continue for at least the coming few months. These groups seem to be capitalising on existing populist sentiment to foment grievances among farmers. Austria, Germany, France, Hungary, and Poland are where this is a particular factor, based on the popularity of these right-wing groups and their performance in recent elections. For example, the right-wing populist Freedom Party of Austria (FPO) had a major hand in organising the country’s first farmers’ protests in January.

Borders highly likely to remain key targets

Blocking borders is likely to remain a key tactic of farmers during protests. This has particularly been the case in Eastern Europe, with countries bordering Ukraine; the main grievance of farmers there has been the perceived flooding of neighbouring markets with Ukrainian products. But similar blockades have also occurred as far west as Portugal, with farmers cutting off key roads leading to Spain.

Border blockades are likely to continue for as long as the protests themselves. But the number of people participating in (and so the disruptiveness of) these is unlikely to rise significantly in the coming months. The number of people participating in border protests is small, suggesting that only farmers based in or near border towns are attending; protests in city centres instead seem to be the events that farmers travel to attend. This is based on our analysis of turnout at protests as well as social media posts organising vehicle convoys from remote towns towards capitals or major cities.

Bottlenecks are highly likely to continue until at least June since each country’s farmers are protesting at different times and affecting border traffic elsewhere. This has particularly been the case with eastern European countries bordering Ukraine. Crossing points have had wait times of up to 48 hours, even at border points where protests are not taking place. This seems to be due to companies having to reroute vehicles for their supply chains away from protests and through alternative crossings; this has been the case in Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia.

Ports and airports also at risk

Seaports and, to a lesser extent, airports will plausibly be affected by protests in the coming months. Protests on major motorways, junctions, or access roads have already caused difficulties in accessing these in many affected countries, particularly Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands. This for the most part does not seem deliberate; we have seen little to suggest farmers are specifically targeting those types of infrastructure, with the exception of isolated cases in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and Romania. Future protests will very probably cause further disruption to accessing airports and ports, for up to a few hours at a time. This is based on our forecast that protests will continue for at least the coming months.

Violence only likely to be sporadic

Farmers are very likely to mostly refrain from violence. We have not seen calls for violence on social media by unions or particularly influential figures, though most are probably using encrypted group chats to communicate and organise.

That said, isolated incidents of violence are more likely than not. This is based on the anger and disempowerment that farmers have expressed on social media around the issue, and that a small subset of protesting farmers appear willing to go beyond peaceful tactics. In Brussels, for example, protesters started fires, threw bottles at police, and let off flash bombs in Place du Luxembourg outside a European Parliament building on 1 February. Police responded with water cannon. The organisers of those protests have threatened more violence in Brussels in the run-up to the EU elections in June unless the EU reverses the policies.

It is unlikely that farmers across the board will resort to deliberately violent tactics, however. Fringe groups seem to have been behind most incidents of violence so far. In Carcassonne, southern France, there was an explosion outside a Ministry of Ecological Transition building on the night of 18 January. But evidence found by the authorities at the scene suggests a long-active group of militant wine producers was responsible; they carried out a similar attack in the same area in 2018. That particular group is well-established and tends to avoid causing harm; the building was empty when the explosion happened.

Image: Tractors during a protest over their conditions and the European agricultural policy near Barcelona on 7 February 2024. The sign reads ‘Our end is your hunger’ in Catalan. Photo by Pau Barrena/AFP via Getty Images.