Acts of politically-motivated violence are almost certain in most states in Mexico over the coming months in the run-up to national elections on 2 June.

This assessment was issued to clients of Dragonfly’s Security Intelligence & Analysis Service (SIAS) on 13 February 2024.

- Candidates for local government positions such as mayors are likely to be the main targets of gang-related violence around the Mexican general elections in June

- Attacks against gubernatorial candidates are plausible but unlikely; most of the hundreds of attacks on politicians ahead of mid-term elections in 2021 targeted local politicians

- We do not anticipate major widespread disruption to the presidential race as a result of gang violence

Acts of politically-motivated violence are almost certain in most states in Mexico over the coming months. This is in the run-up to national elections scheduled for 2 June. Organised crime gangs have frequently attacked candidates and other political figures ahead of previous polls. This year is unlikely to be any different. We assess that businesses will probably not be affected by attacks, based on established patterns and the aims of such groups. Incidents are likely to involve targeted shootings in rural areas or on the outskirts of urban areas. But there is a strong possibility of some isolated attacks in central areas of large cities, including Guadalajara and Tijuana.

Pre-election violence is likely to be most common in states where organised crime is already a major issue. In-country security contacts have told us in recent years that gangs mount attacks during campaigns to pressure candidates not to make anti-crime pledges, thereby protecting their illicit activities. Based on recent conversations with our sources, reported incidents of ongoing gang turf wars and Mexican press reports, we assess that incidents of this type will be particularly prevalent in the following states:

| • Chiapas | • Colima | • Guanajuato |

| • Guerrero | • Jalisco | • Mexico state |

| • Michoacan | • Tabasco | • Tamaulipas |

| • Veracruz | • Zacatecas |

This type of violence is also likely to take place but less frequently in:

| • Baja California | • Chihuahua | • Morelos |

| • Puebla | • Quintana Roo | • Sonora |

A particularly violent election period looms

There is a track record of electoral violence in Mexico. There were hundreds of attacks on politicians ahead of mid-term elections in 2021, but this year we anticipate that there will be even more such incidents. There are two reasons for this; first, organised crime groups appear to have become more brazen in their shows of force in recent years. For example, gangs have mounted several indiscriminate attacks in response to security operations against them. Gangs will almost certainly try to influence elections to ensure that incoming administrations – particularly at the state and municipal levels – facilitate (or at least tolerate) their illicit activities.

A second reason is that there will be an unusually high number of elections across Mexico this year. More than 20,000 positions are up for grabs on 2 June, almost six times the number of posts renewed at the 2018 general elections. Of these, close to 20,000 are municipal government positions and state legislative seats. Candidates for mayor and other local positions have been at greatest risk of being targets of gang-related political violence.

There are also eight states where voters will elect governors: Chiapas, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Morelos, Puebla, Tabasco, Veracruz, and Yucatan. And voters in the capital Mexico City will elect a new head of government. However, precedent and the gangs’ key objective to gain advantages that facilitate their operations at the local level, suggests that they are unlikely to target candidates for governor.

The tempo of attacks will probably rise significantly after campaigning starts in March. For federal candidates, this is at the beginning of the month, while other races start towards the end. Data Civica, a local NGO that tracks political violence related to organised crime, calculated there were 574 such incidents during 2023, the highest number for five years. It also recorded five murders of candidates during January. We expect that similar incidents will occur more frequently into March, particularly as the candidate selection process concludes (for many state and municipal positions, this will be on 17 February).

Attacks likely to be targeted rather than indiscriminate

We assess that there is a low risk of most businesses and travellers being caught up in most acts of electoral violence. Potential incidents would almost certainly be targeted shootings of candidates and public officials. Organised crime groups’ motivation to interfere in the election is to secure control of local authorities within their territories of interest rather than terrorise the population, for example by killing large numbers of people. And mass casualty attacks typically prompt larger deployments of security forces that are disruptive to their operations.

Attacks would most likely involve close-range killings of individuals or attacks when they are on the move. These typically happen out of, or in the outskirts of, towns rather than in central areas. This was the case of Marcelino Ruiz Esteban, who was seeking to become a candidate for mayor of Atlixac in Guerrero. He and his wife, also a local politician, were killed on 24 January on the Chilpancingo-Tlapa road, reportedly by an organised crime group.

The risk of indiscriminate shootings at crowds in urban areas is low. Gangs are also unlikely to use explosive devices, including those deployed by drones, in these areas. While they have the capability to carry out such attacks, they have only done so against rivals and security forces, particularly in response to authorities’ actions. This was the case of a bombing by the Familia Michoacana on 4 January in a remote rural area of the Heliodoro Castillo municipality in Guerrero as a result of its turf war against the local gang Los Tlacos. Local press outlets reported that the attack targeted some 30 men and only five people survived.

We do not anticipate that rates of violence will increase significantly in areas of Mexico frequented by business personnel and travellers. In our assessment, incidents of gang-related electoral violence in Mexico City are most likely in eastern boroughs such as Gustavo Madero, Iztapalapa, Azcapotzalco, Tlahuac and Xochimilco, in the south. It is plausible that incidents of violence could also take place in the central Cuahutemoc borough, where the historic city centre and many government buildings are located. However, these would be most likely to happen in low-income areas not usually visited by business personnel.

Major disruption improbable

We assess it is highly unlikely that violence during campaigning would disrupt the elections in June. This is particularly the case regarding the presidential election. The only case in recent times that a presidential candidate was killed did not delay or stop the process. After the ruling party’s candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio was murdered at a rally in Tijuana in March 1994, his replacement was swiftly appointed and went on to win the election in August of that year, as scheduled. The most widely accepted explanation is that his death resulted from internal power struggles within his party, rather than having been a target of organised crime.

Incidents of violence on polling day are likely to remain localised. This is because of the motivation behind the gangs’ involvement in electoral violence, which is to enable them to carry out their activities without obstacles at the local level. In previous elections, the Electoral Court (TEPJF) has annulled the results of polling booths in some electoral districts due to violence. This was the case in four municipalities of Michoacan in the mid-term elections of 2021. However, the overall security and political impact of these cases was limited. And we expect the situation to remain the same this year.

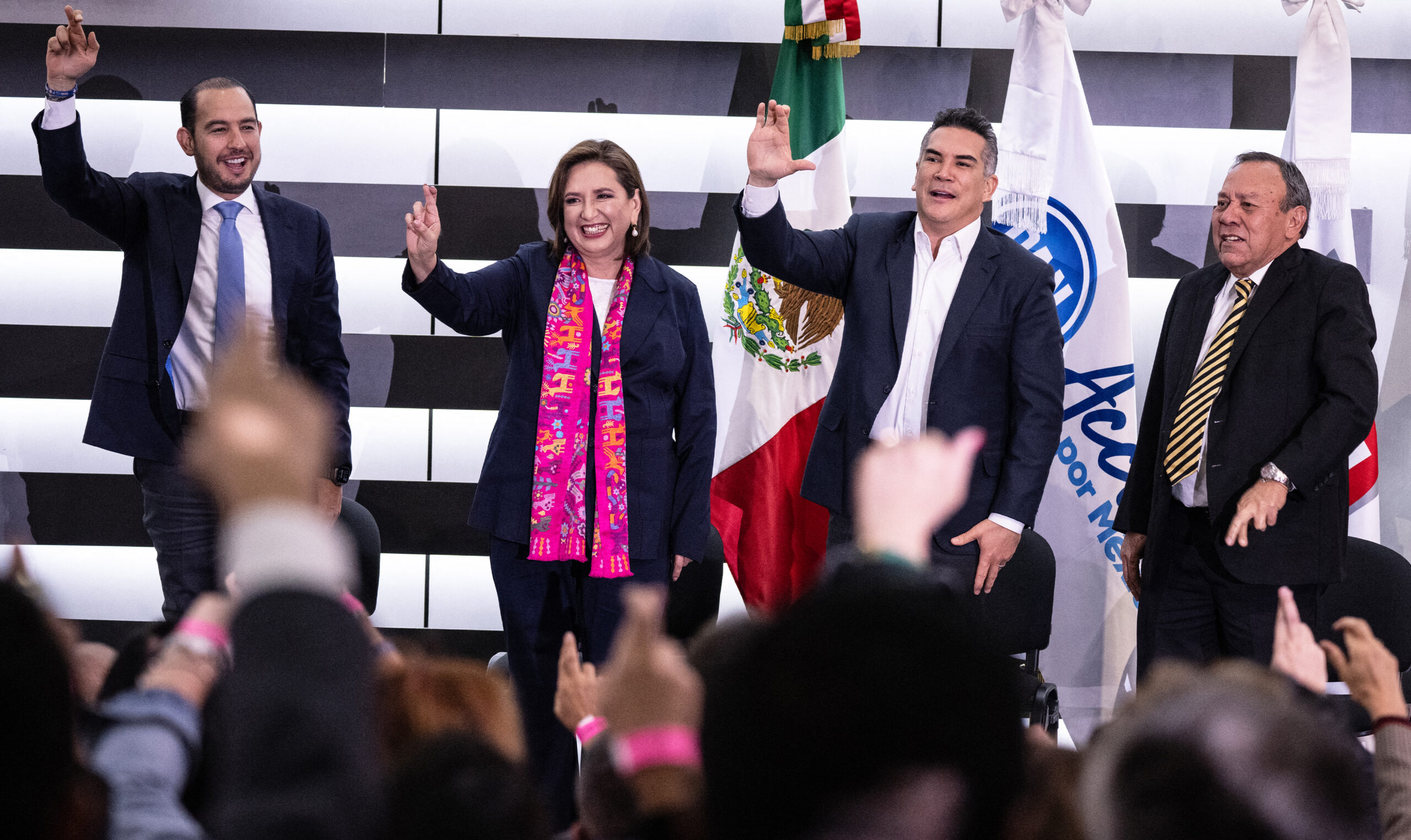

Image: Opposition candidate Xochitl Galvez (2-L) of the Fuerza y Corazon por Mexico coalition party stands next to the President of the National Action Party (PAN), Marko Cortes (L), the President of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, Alejandro Moreno (2-R), and the President of the Democratic Revolution Party PRD, Jesus Zambrano (R), at the National Electoral Institute (INE) in Mexico City on 20 February 2024. Photo by Carl De Souza/AFP via Getty Images.