Pakistan will probably avoid a major economic crisis this year, amid a degree of economic stabilisation linked to IMF assistance

This assessment was issued to clients of Dragonfly’s Security Intelligence & Analysis Service (SIAS) on 21 May 2024.

- Still, economic conditions remain tough for much of the population, which will probably sustain a high risk of protests and social unrest

- Enduring economic challenges and social tensions mean that the economic and political pressures on the government are likely to rise over the long term (within five years)

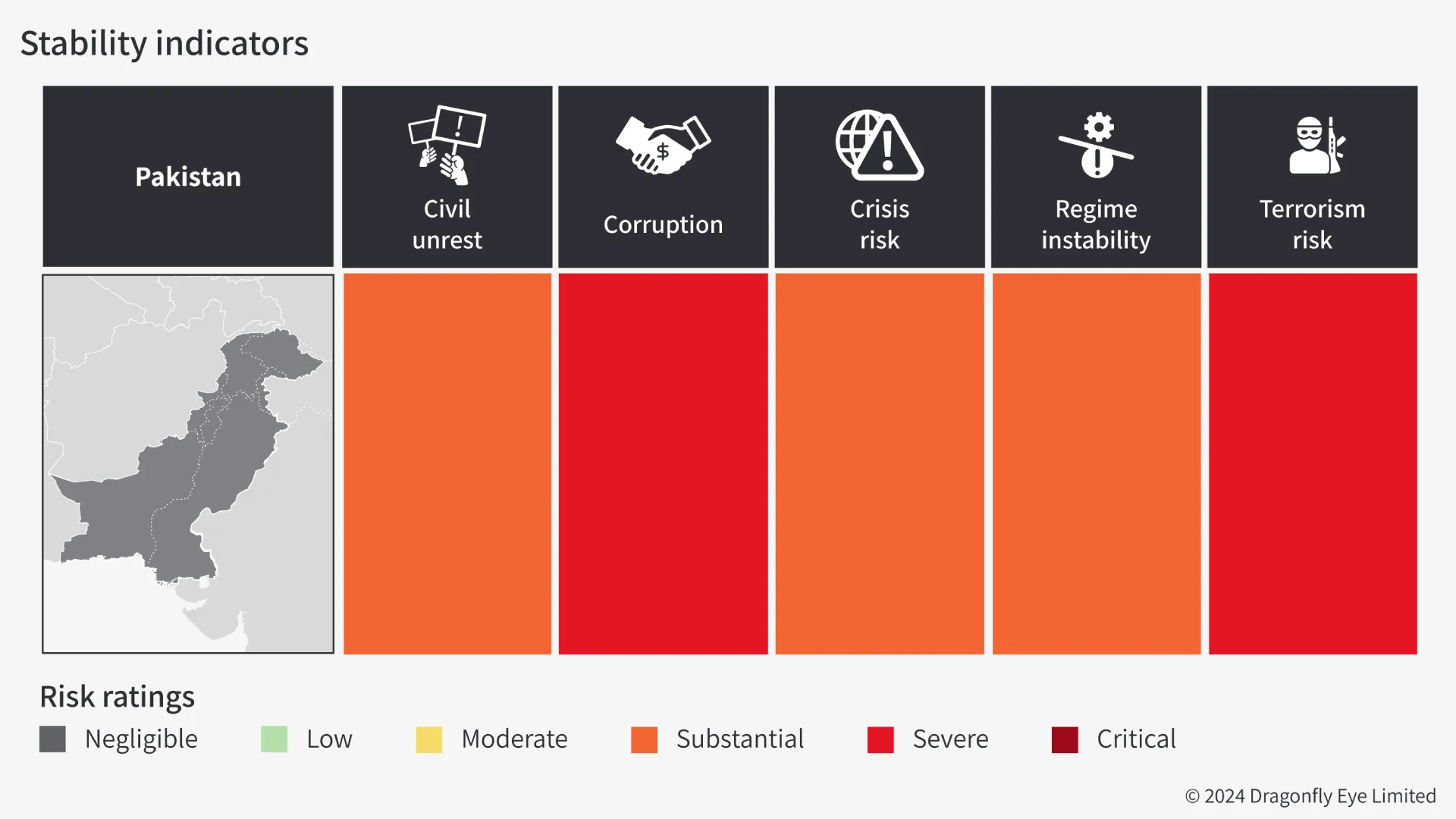

The governing coalition in Pakistan is likely to avoid a political and economic crisis in 2024. The economy has stabilised in the past year with the help of the IMF. Still, tough economic conditions will probably sustain protests and social unrest over the medium term (up to one year); the opposition has proven capable of capitalising on widespread popular frustration in these conditions.

While we doubt that such protests will greatly affect government stability in 2024, more serious political and economic crises are probable over the next five years. And we predict that the government will collapse before the next election, which is due in 2029. That is because persistent debt-repayment pressures, entrenched economic problems and a continuing cost-of-living crisis are likely to sustain pressure on the economy and on a relatively fragile government.

Economic conditions stabilising for now

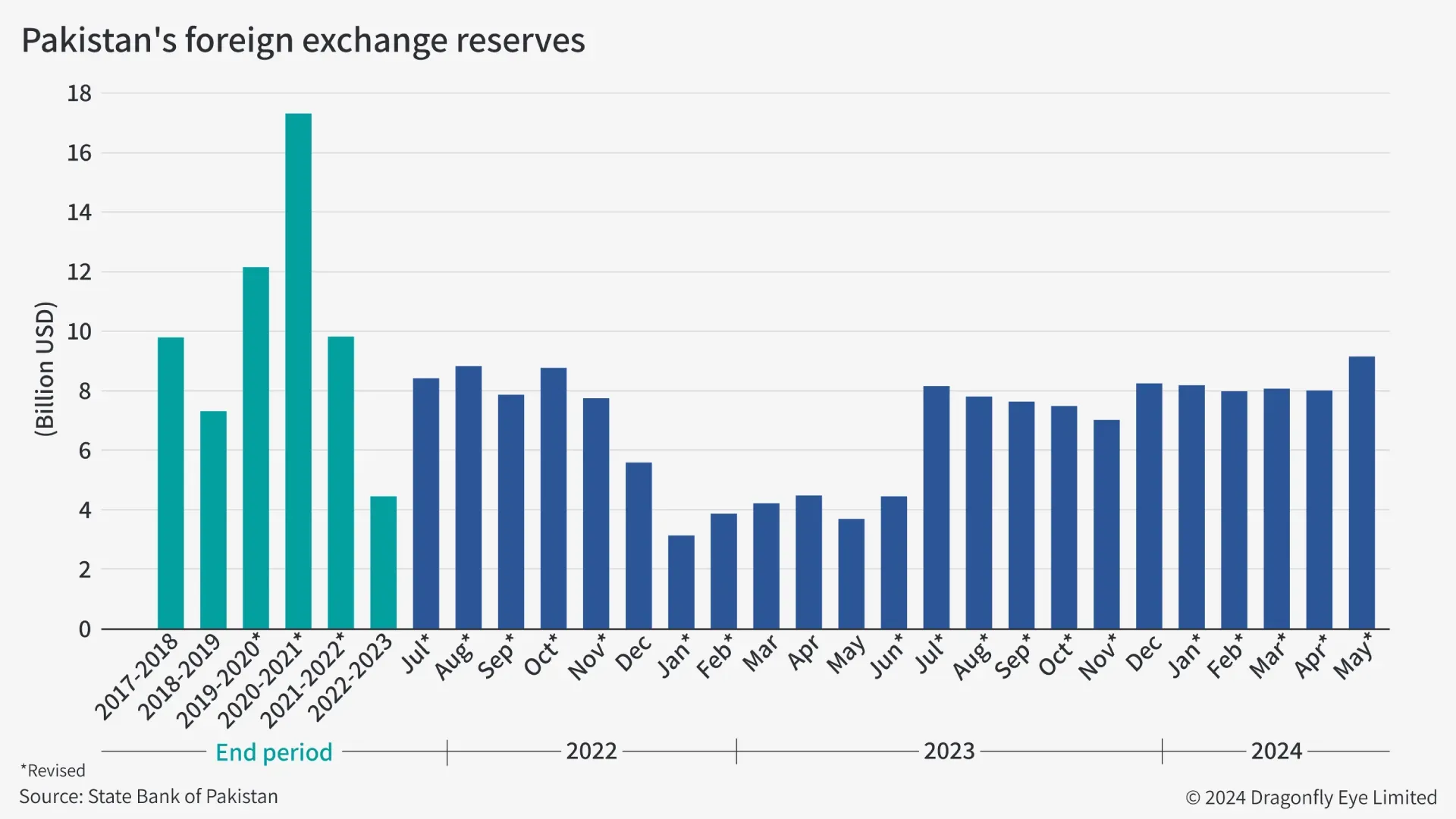

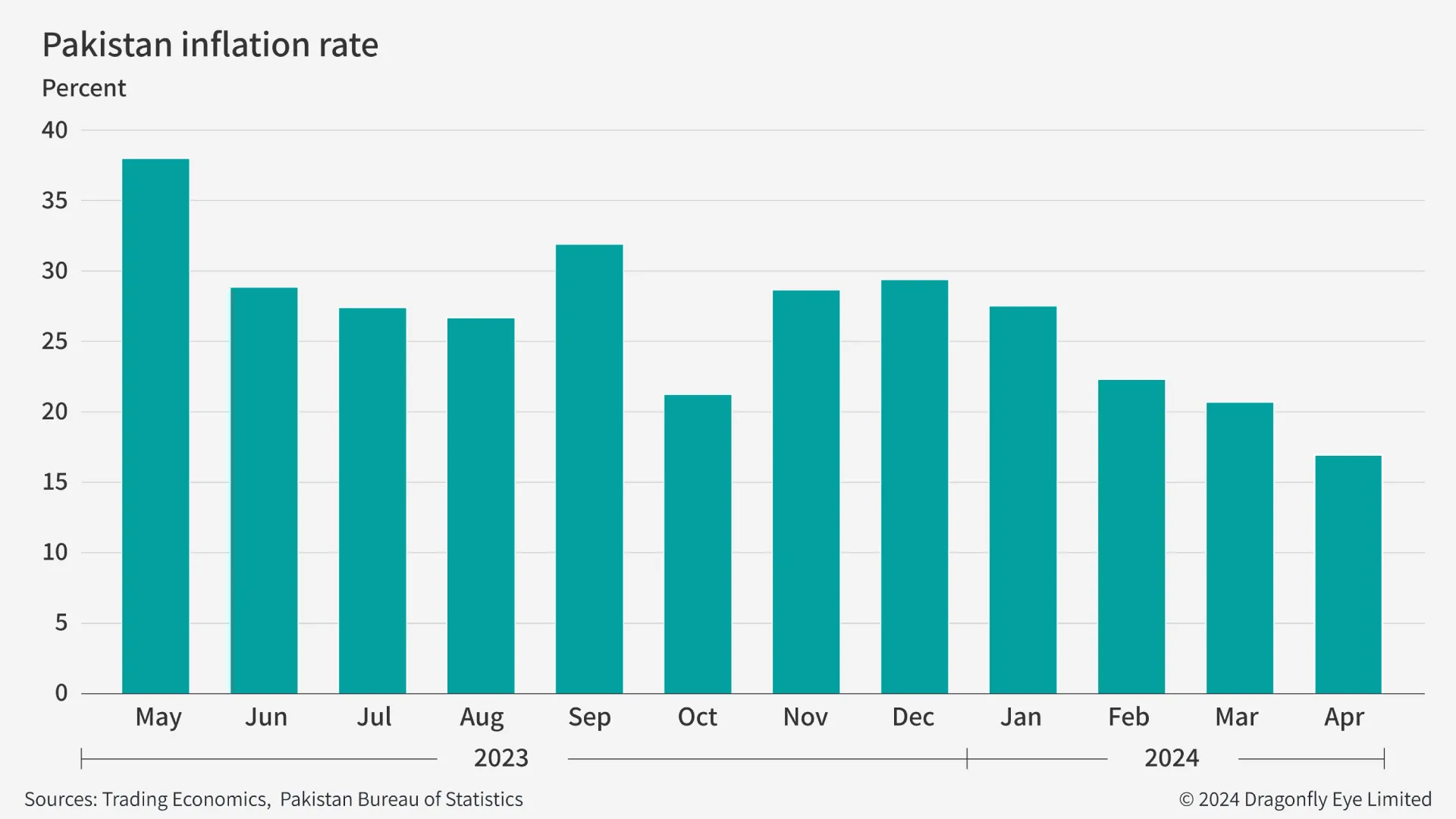

Pakistan is likely to avoid an acute economic crisis in 2024. The economy has stabilised in recent months. Foreign exchange reserves have grown and inflation slowed (see the charts below), largely owing to the measures taken by the government to secure a $3 billion IMF loan last July. The IMF approved the release of the final $1.1 billion to the government on 29 April. This will help it repay $3.5 billion of foreign debt due by June, so limiting the chances of the government restricting capital flows and goods imports. And based on their recent statements, the IMF and Pakistan are likely to agree to a new, larger IMF loan by early July to address medium-term macro-financial weaknesses.

But key economic indicators continue to point to a sustained risk of social unrest. The World Bank in early April forecast a recovery in the economic growth of Pakistan in 2024 to only 1.8% (from around 0.4%in 2023). According to the World Bank, this is linked mainly to ‘scarce foreign reserves, and muted economic activity amid weak confidence’. Pakistan still has the highest inflation rate in Asia (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics said 17.3% in April), and reportedly (CEID Data) still only had enough reserves to cover the country’s import bill for 2.6 months in March 2024. This is still below the minimum safe level of three months’ import cover. And the central bank warned last week that any increases in energy prices would offset the recent positive developments.

But key economic indicators continue to point to a sustained risk of social unrest. The World Bank in early April forecast a recovery in the economic growth of Pakistan in 2024 to only 1.8% (from around 0.4%in 2023). According to the World Bank, this is linked mainly to ‘scarce foreign reserves, and muted economic activity amid weak confidence’. Pakistan still has the highest inflation rate in Asia (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics said 17.3% in April), and reportedly (CEID Data) still only had enough reserves to cover the country’s import bill for 2.6 months in March 2024. This is still below the minimum safe level of three months’ import cover. And the central bank warned last week that any increases in energy prices would offset the recent positive developments.

The government’s efforts to meet IMF loan conditions in 2024 will probably stoke public grievances. A contact in the financial sector in Lahore told us earlier this year that many people faced difficulties paying electricity bills following several price rises mandated by the IMF, which came on top of already high food price inflation. Based on recent IMF statements and previous agreements, the government will probably have to implement further cuts in energy and fuel subsidies, and increase taxes, to continue to qualify for IMF aid in the years ahead. Local press reports suggest low- and middle-income social groups would be worst hit.

More hardship protests likely

These measures are likely to sustain frequent protests countrywide over the coming year. In the latest instance, several thousand people in the northern state of Azad Kashmir protested over high prices of flour and electricity on 8-14 May. While the organisers have since called off these protests, similar grievances will probably lead to protests, particularly in poor regions such as Balochistan. Between a few hundred to several hundred people would potentially also gather in major cities in response to any fuel or electricity price hike, as happened in August 2023. The opposition parties are almost certain to capitalise on public frustration to put pressure on the government, including by calling for protests.

We doubt that such protests will lead to major episodes of civil unrest. Or that these would threaten the government in the coming year. While the protests in Azad Kashmir sparked violent clashes with the police and led to four deaths, in our view, discontent over the region’s semi-autonomous status also contributed to this. And although there is a precedent for hardship protests in major cities turning violent (from 2008, 2015 and 2018), major riots are rare. Most opposition rallies and hardship protests in recent months have been relatively peaceful, with a few isolated violent incidents at most. The authorities are largely capable of containing any disorder and the high risk of arrest seems to be an effective deterrent.

Longer-term economic and political pressures likely to build

Over the next five years Pakistan faces ingrained economic problems. Those include low productivity and a high unemployment rate, which will be difficult and probably painful to address, underpinning the prospect of an economic crisis in the coming years. Irrespective of any new IMF loan, pressure on foreign reserves and long-term debt default risk will remain. This is because of Pakistan’s reliance on imported fuel to meet its energy needs, as well as a looming debt bill of $77.5 billion which must be paid by 2026. That would be a considerable outflow of resources relative to the size of Pakistan’s economy.

In the coming years, economic pressures will probably undermine the governing six-party coalition, affecting government stability. This further depends on the prime minister’s ability to maintain parliamentary backing for his economic reforms from the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP). The coalition has only a slim majority and is likely to face contestation of reforms from the opposition. But while the PPP chair has said he will ‘support’ the government, he has not joined it. And based on their previous cooperation and differing ideologies and interests, we anticipate that PPP support is unlikely to last, making the government vulnerable to collapse before the next general election is due in 2029.

Image: A Pakistani man counts Pakistan’s rupees at his shop in Karachi on 16 May 2019. Photo by Asif Hassan/AFP via Getty Images.