Within the region, there are six countries that would be vulnerable to shortages in the event of a shutoff of gas flows. In descending order of impact, these are: Hungary, Czechia, Slovakia, Italy, Austria and Germany.

This is based on projections by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and our analysis of regional natural gas usage, current storage levels and diversification efforts.

We have summarised what we assess would be the impact of a complete cut-off of gas from Russia in each of these six countries (these assessments are developed further later on in the report):

- Hungary: shortages to all industrial sectors and households within weeks

- Czechia: shortages to all industrial sectors within weeks

- Slovakia: unlikely, minor shortages for businesses in the months after a cut-off

- Italy: shortages unlikely over the next year

- Austria: shortages for businesses unlikely

- Germany: rationing highly unlikely to affect industries over the long term

Projected shortfalls

An IMF study in July is the most comprehensive available analysis of the potential implications of Russian gas flow disruption for Europe. It takes into account diversity of imports (until July), energy mixes, current gas reserves, and existing supply bottlenecks to produce a stylised ‘worst-case scenario’ projection for gas supply in the event of a cut-off of all Russian flows. It acknowledged that the impact on gas supply would ‘likely differ across regions’ due to their ‘different alternative supply possibilities’. But it highlighted that the period where demand would outstrip supply by the furthest margin would be between mid-March and mid-May 2023.

The IMF’s graph above shows a projection of how gas storage levels in Europe might have looked if Russian imports had continued as they were in July. The lower, dotted line shows how gas levels might look in a Russian ‘shut-off scenario’. The lower line illustrates the IMF’s projection that, from mid-February until mid-June 2023, demand for gas in European countries will likely be higher than they can produce, import, or draw on from reserves. This would suggest that demand would need to fall by up to 20% across Europe to avoid shortages.

The lower-line IMF projection assumes only that each country shares its ‘excess’ inventories with others in the region. The EU has pledged but not yet clearly defined this scheme. But the IMF’s forecast does not account for any successful import diversification in the time since publication. Because of this, the current outlook in terms of how much countries would need to reduce demand is probably more positive now than when the IMF was conducting the analysis. But we still consider the IMF’s projection to be indicative of vulnerability to shortages, and useful to use in a worst-case-scenario assessment.

Drastic cuts needed?

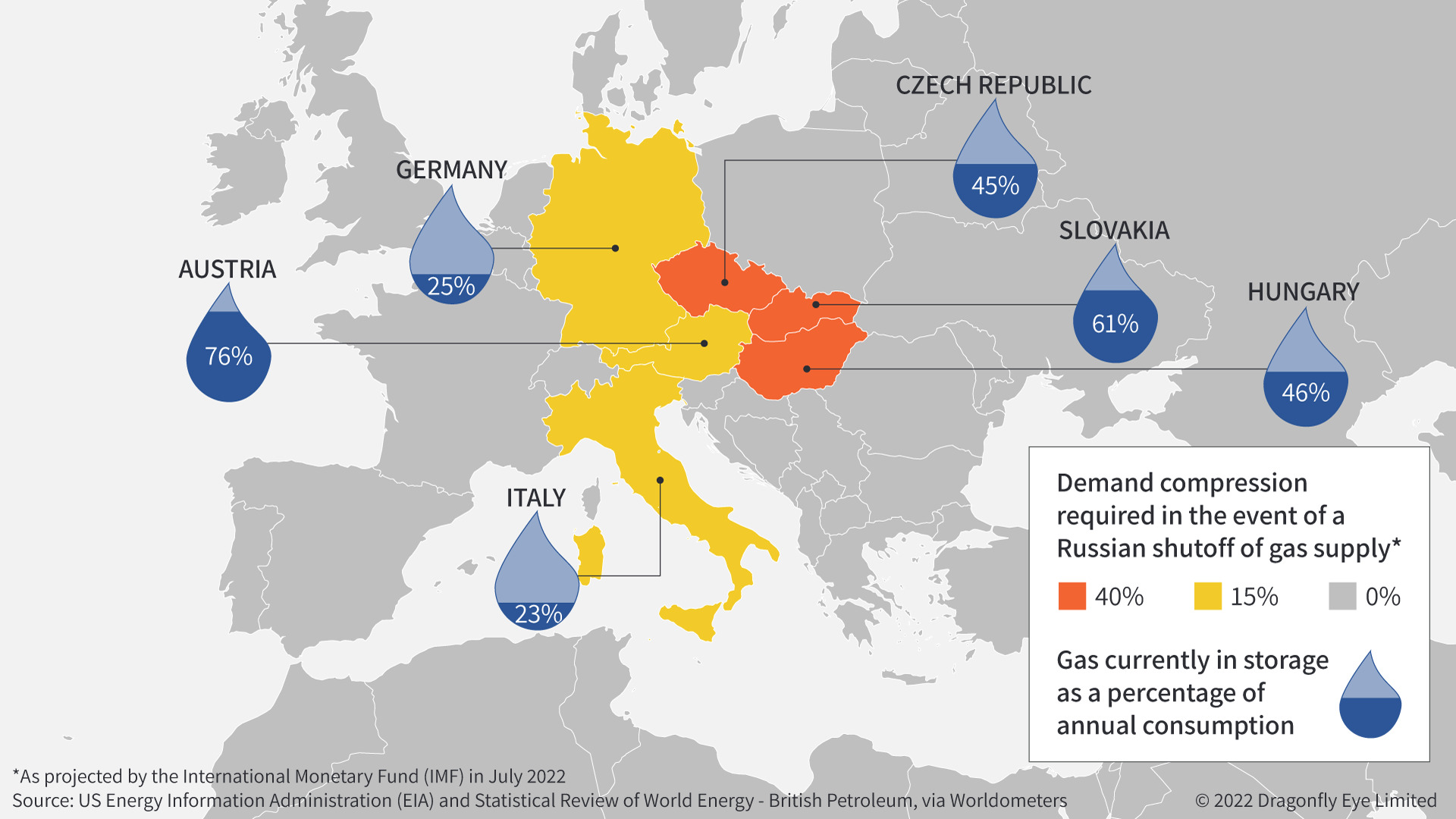

The report projects that Czechia, Hungary and Slovakia are most vulnerable to a cut-off of Russian gas flows. It projects that these countries would need to reduce demand for gas at the national level by 40% to avoid shortages in a worst-case scenario. It estimates that Austria, Germany, and Italy would have to reduce demand by 15%. The map above also shows the volume of gas that each country currently has in storage as a percentage of total annual consumption; that is, how much of each country’s gas requirements for next year could hypothetically be covered just by the amount currently in storage.

Likelihood of shortages and vulnerability of sectors

Czechia

Czechia would be very likely to experience shortages in the event that Russia cuts off gas to Europe. This is due to its continued dependence on Russian gas (the International Energy Agency said in August that it still relied ‘mostly’ on Russian imports) combined with the relatively insufficient increase in alternative gas sources. In July, it reached an agreement with the Netherlands to provide an additional 3 bcm of gas capacity – roughly a third of Czechia’s total annual consumption – through a new terminal and transit routes. For now, however, the country currently has the equivalent of only 45% of its annual gas consumption in storage.

We assess that the government would almost certainly prioritise supplying ‘protected customers’ in this event, which includes households. Due to this, and a requirement on suppliers to maintain reserves, it seems probable that the authorities would in the first instance seek to ration the supply of energy to industries involved in the production of non-metallic materials (more than 25% of the share), food, drinks, tobacco, and chemicals. That is also since the government has already taken other steps to cut consumption, including allowing heating plants to use other fuels instead of gas.

Hungary

Hungary is similarly extremely dependent on Russia and would be critically vulnerable to shortages in the event of a total shutoff. Seemingly for political reasons, it has taken even fewer steps than Czechia to diversify supply. The country currently has the equivalent of only 46% of its yearly gas consumption in storage, and continues to rely on Russia for between 85% and 90% of its total supply. And at the end of August, Hungary agreed on a new deal to more than double its supply volume through one pipeline from Russia.

The country’s plans for how and where to ration energy are not well developed either, at least based on what the government has said publicly. This means that gas supplies are therefore very likely to be uncertain for businesses, which could potentially lead to operational disruption, in the first half of 2023. For example, the government has announced plans to reduce consumption by 25% to reduce pressure on supplies. A government official earlier this month said the reduction will be mandatory for public institutions but ‘industry will start using less on its own’, without providing details.

Slovakia

In Slovakia we do not anticipate that even the most unprotected businesses would suffer significant impact in the event of a shutoff. That is even though as of July, Slovakia imported around 86% of its gas from Russia. The country currently has the equivalent of around 61% of its yearly consumption in storage. A new gas pipeline with Poland launched at the end of August also now gives Slovakia access to an additional 4.7 bcm per year (87% of its yearly consumption). Together these measures indicate that the country is already well-equipped to tackle any hypothetical supply shutoff from Russia.

Austria

Businesses in Austria will probably be largely shielded from any risk of shortages in the near and long term. Even in a worst-case scenario, the government said in May that it plans to exempt large industrial companies, as long as storage levels stay above 50% of annual consumption. The country currently has the equivalent of 86% of its yearly consumption in storage; this alone makes it extremely well positioned to manage if Russia halted all supplies.

Austria also reduced its dependency on Russian gas from 80% to 50% as of August. It has also proposed plans to help speed up supply diversification through an annual support package of around €100m to support companies’ transition away from gas.

Germany

German manufacturing will probably see some rationing. But measures that the government have put in place are such that these are unlikely to involve business-critical shortages, even for the most energy-heavy companies (such as chemicals, metals, food and tobacco). Germany is currently on the second stage of a ‘gas emergency plan’; at stage three, it has said it will begin to ration gas to ensure supply to its ‘protected’ consumers, which are households (mandatorily protected across the EU) and healthcare facilities.

The government has said that the first sector to see rationing would be manufacturing. It started preparing for a Russian shutoff scenario in July, and the measures appear to have been effective. It implemented a scheme that allows companies to decide when they can cut or suspend use of gas, greatly reducing the likelihood that the national regulator will switch off supplies to companies even in the event of severe shortages. The scheme mandates that the extra gas saved be shared between all industries, greatly reducing the likelihood of disruptive shortages, provided this can be executed effectively.

Italy

The risk of shortages to businesses in Italy is relatively low – evening in a worse-case scenario – over the coming months. The government has ruled out rationing, but has already announced plans to cut consumption by 7% until March 2023 by reducing heating in private residential and public buildings. A government minister said in July that the country had enough gas to last until February 2023 even if Russia cut gas flows at the beginning of the winter. As for import options, Algeria has now replaced Russia as Italy’s main source of gas.