A reduction in sea ice is very likely to lead to competition over access to resources and shipping routes in the polar regions this decade.

This assessment was issued to clients of Dragonfly’s Security Intelligence & Analysis Service (SIAS) on 20 February 2024.

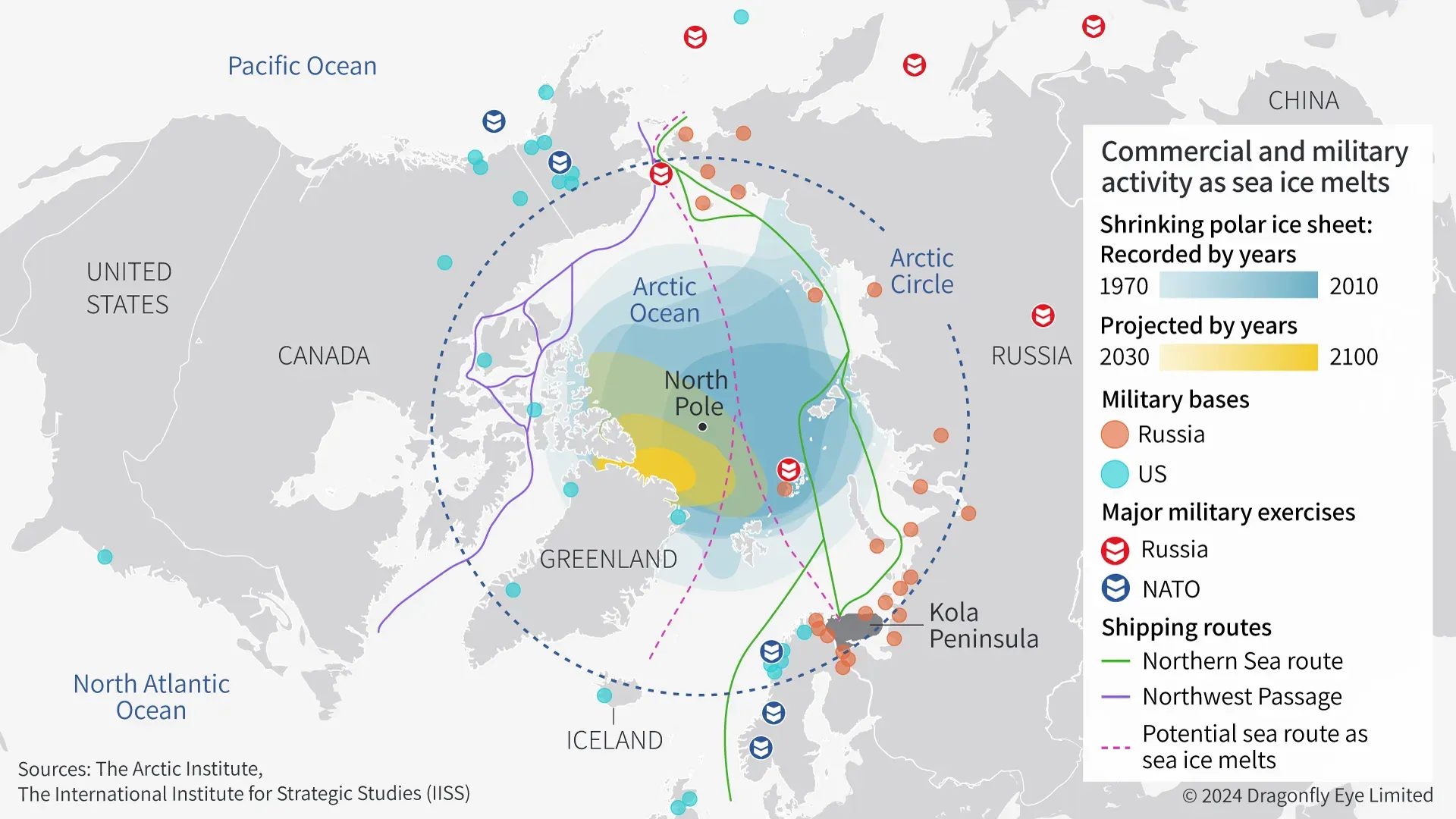

- Arctic sea ice has declined by about 10% over the past two decades and projected further melting could open up important new shipping lanes

- Some states are already expanding their military presence within these regions, most probably to secure their commercial interests

Competition between major powers over the polar regions is highly likely to intensify over the next five years and beyond. Climate change-induced melting of Arctic sea ice and Antarctic ice sheets is altering fish stocks, uncovering new shipping routes and making accessible vast natural resources. China, Russia, and the US are already jostling over these opportunities, which will very probably spur further diplomatic and military tensions in those regions.

Among the global knock-on implications for anyone considering security and political risks for their organisations are:

Among the global knock-on implications for anyone considering security and political risks for their organisations are:

- Uncertainty and volatility around new trade routes in the High North

- Governments incentivising to invest in those regions, notably in the extractives, energy, logistics and defence sectors

- New geographies (Arctic and Antarctic) to monitor for signs of US-Russia-China competition – or indeed escalation

However, war between the US and Russia or China in the polar regions remains highly unlikely over the next decade.

Competition between major powers will be largely economic

China, Russia and the US among others are seeking financial gains from the polar regions. Melting Arctic sea ice will probably provide access to shipping lanes that would shorten travel times between Europe and Asia for some cargo vessels by about 40%. According to the US National Intelligence Council, an estimated $1 trillion worth of metals and minerals will become more available in the Arctic region due to projected environmental changes. Those are essential for manufacturing batteries and semiconductors.

It is plausible that Antarctica will become a key source of food and water in the coming decades. As food systems and freshwater reserves come under strain due to environmental and demographic shifts, fishing activities in the Southern (Antarctic) Ocean are likely to become a focus of competition. China is already actively cultivating Antarctic krill. And some states will probably view Antarctica’s ice resources as offering a solution to their freshwater demand.

Establishing control over these regions would enable countries to secure influence, particularly over international trade flows. Russia, for example, requires permits and levies fees for passage through the Arctic’s Northern Sea Route. And those countries that provide the necessary infrastructure to support Arctic shipping activity are likely to benefit from more sea traffic as melting ice opens up new routes (see map above).

Militarisation in the polar regions

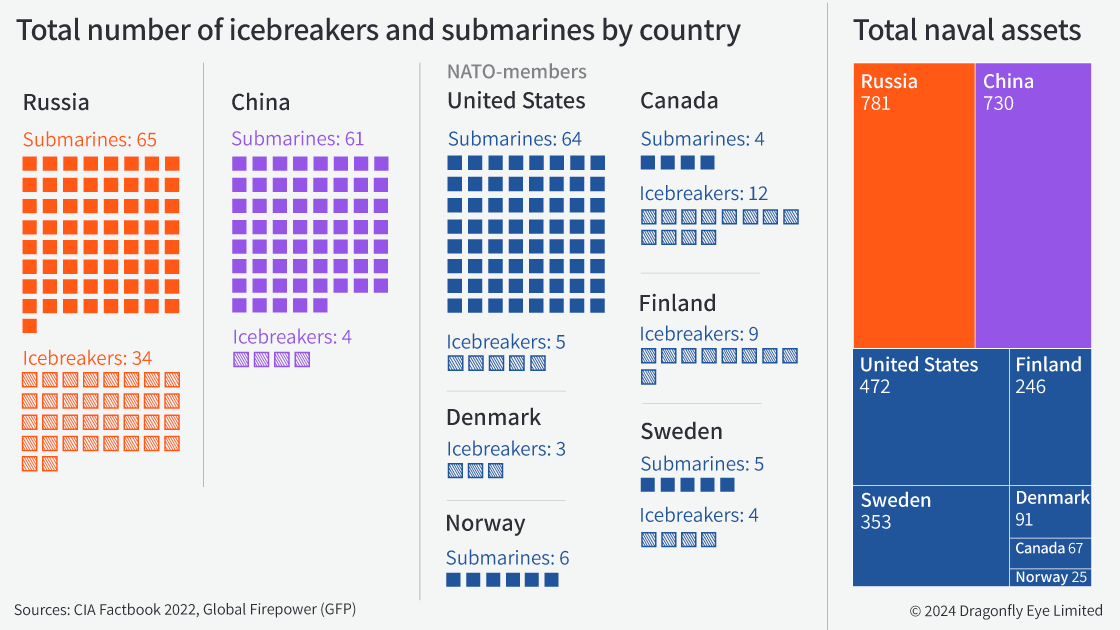

Major powers will probably seek to establish or expand their military footprint within these regions to help secure their nation’s commercial and security interests. A new Arctic Strategy, scheduled to be released by the US Department of Defence in early 2024, will almost certainly involve investment in Arctic military capabilities. Decades of relative US neglect – while Russia continued to invest in the area – have resulted in a considerable discrepancy between the two powers’ security capabilities there. Russia’s icebreakers, for example, outnumber those of the US seven-fold.

Russia is likely to try to maintain its dominant position in the High North. Its territory stretches over 53% of the Arctic coastline. And efforts by its government include securing both the Northern Sea Route and its sea-based nuclear deterrent capability in the Kola Peninsula. Moscow has over the past two decades reopened tens of Soviet-era Arctic military bases, modernised its navy, and developed new hypersonic missiles designed to evade US sensors and defences, according to international media reports.

China will probably deepen its coordination with Russia on Arctic affairs. This is because Beijing has no territorial sovereignty in the Arctic. Recent cooperation has included Chinese investment into Russian projects along the Northern Sea Route, and joint Arctic naval exercises passing near Alaska as recently as in August 2023. Some 234 Chinese companies registered to operate in Russian Arctic territory from January 2022 to June 2023 which, according to data cited by Canadian paper The Globe and Mail, was 87% more than in the two years prior.

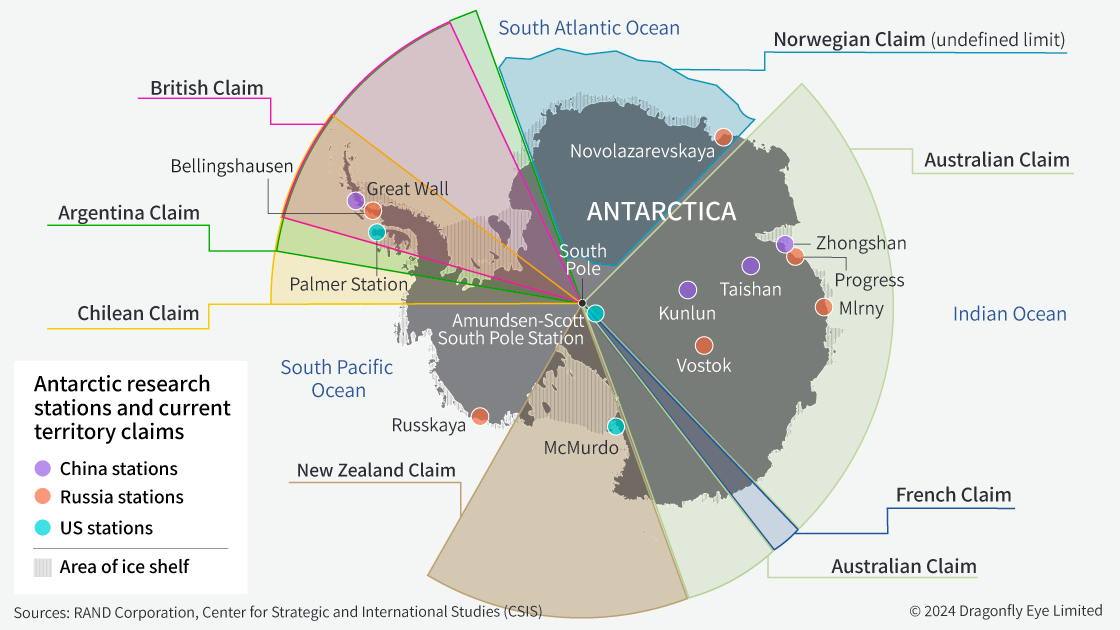

The Antarctic is likely to remain far less militarised, not least due to its remoteness. Yet China, Russia and the US will almost certainly continue to develop dual-use facilities that combine scientific research and military functionality. The US in October 2022 claimed that China was using scientific programmes for covert intelligence collection. And China’s National Defense University has identified, in a 2020 publication, that ‘military-civilian mixing is the main way for great powers to achieve a polar military presence’. But it is more likely than not that Russia and the US among others have a similar strategy.

Interstate conflict risk is low this decade

War between the US and Russia or China in the polar regions remains highly unlikely, however, over the next decade. This is because Russia’s military efforts are currently focused on Ukraine, and US or Chinese capabilities are far behind. Still, militarisation combined with polarisation between NATO countries and Russia and China means that crises short of war are probable during the next few years and beyond. Such crises would probably, for example, feature:

- Military posturing by moving or deploying at least several hundred additional troops

- Training exercises near or in other states’ maritime territories and displays of capabilities such as live fire drills

- Sabotage of infrastructure, such as subsea cable

Future economic activity in the polar regions would be vulnerable to disruption in case of any dispute over resources or territory there. That includes trade passing through and local extractive industries and is because major powers would be likely to settle their differences through sanctions or blockades. There are few robust or effective international governance mechanisms to resolve disputes of this kind.

Governance frameworks outdated and ineffective

Arctic and Antarctic governance frameworks appear strained. So already limited diplomatic options for de-escalation will probably shrink further in the coming years. Russia, following its invasion of Ukraine, has been shunned from the Arctic Council – which pending Sweden’s accession now consists fully of NATO states. This complicates agreements on sustainable development and environmental protection in the region. And it further incentivises Russian cooperation with China.

There is a reasonable chance that the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) will be rendered redundant in the coming decades. The ATS designates the continent as a scientific preserve, banning military activity. It also maintains a focus on environmental preservation over exploitation. However, it lacks any means of enforcing these provisions and freezes rather than resolving any competing territorial claims. And while the Antarctic is becoming more accessible due to climate change and technological advances, the ATS does not reflect current-day power dynamics.

Antarctic governance arrangements are likely to further weaken as 2050 approaches. This is when the current ATS is formally up for review. China and Russia, in particular, are likely to attempt to shift the ATS toward economic exploitation over environmental conservation and may seek to revitalise the issue of territorial claims. The discovery of critical minerals or other highly valuable resources would be likely to accelerate this timeline.

Wider implications of polar-focused competition

Competition in the polar regions appears likely to feed into broader geopolitical volatility. As some states spend more time addressing strategic competition in the polar regions, they will have less time and resources to deal with other geopolitical issues – meaning that the effects will be felt in other seemingly unrelated areas. This trend will probably compound existing tensions between states that are already contributing towards a more challenging international business environment. This will almost certainly drive up the level of uncertainty and risk organisations face.

Image: Sunset on the ice with cracks. Lake Baikal, Irkutsk Region, Siberia, Olkhon Island on 20 March 2018. Photo by Anton Petrus via Getty Images.